We’ve heard a lot about fuel emissions standards recently, but there are actually several moving parts to this concept – these being vehicle (tailpipe) emissions controls and vehicle greenhouse gas reduction targets. In addition, there is a third variable – for they both rely on the quality of fossil fuel poured into the tank of internal combustion engine (ICE) vehicles.

Therefore, the full picture looks like this – in order you need:

- Fuel quality standards;

- Vehicle (tailpipe) pollution controls;

- Vehicle greenhouse gas reduction targets.

(Note: The first two fall under the umbrella of vehicle emissions standards according to the Electric Vehicle Council, while the last is also known as fuel efficiency targets.)

Here in Australia, we fail on all three. The rest of the world has long passed us by in setting cleaner fuel standards, lower levels of acceptable tailpipe pollutants and they continue to set ever lower targets for overall vehicle greenhouse gas emissions. In the long run, as these targets are lowered the ICE vehicle naturally phases out in favour of electric ones.

For Australia to act on any one of these steps alone, we could end up with quite perverse outcomes that do not encourage manufacturers to bring their lowest polluting ICE vehicles along with greater numbers of the lowest polluting of all vehicles – the BEV (full-battery electric vehicle).

So let’s look at each in turn and how they relate to each other – and why not acting on all three together could create these perverse outcomes:

1. Fuel quality standards

Currently, Australia’s fuel quality standards are the worst in the OECD for both sulphur and ‘aromatics’ contents.

If you are wondering why sulphur is a problem: high sulphur levels result in contaminated vehicle catalytic converters (part of vehicle exhaust systems since the 1980s), limiting their ability to convert pollutants – including the health-harming nitrogen oxides – into less harmful ones. In addition, some newer ICE engine and emission control technologies need low sulphur fuel to operate effectively.

That is not the end of the fuel quality problem though. Australia is also equal worst (with New Zealand) for ‘aromatics’. (‘Aromatics’ being a general term for benzene and its derivatives).

A high aromatic content in petrol can result in the formation of deposits within the engine, resulting in higher particulate and other carcinogenic pollutant emissions. Lowering aromatics in petrol also improves engine performance.

Currently, Australia is ‘on track’ to adopt better fuel quality and vehicle emission standards – but the previous Liberal government managed to put in place a very drawn-out process to get there.

Under their policy (which is still in place) – fuel quality is to be gradually improved to the currently existing world standard by 2027. At that point (and only at that point) is Australia move to Euro 6d vehicle emissions standards. This will put us well over a decade behind the rest of the world for both.

This lead-time was argued for by the then federal government in their submission to the Draft Regulation Impact Statement: Light Vehicle Emission Standards for Cleaner Air (by the Department of Infrastructure, Transport, Regional Development and Communications), in order to “provide refineries with certainty for major investment decisions and allows them to plan workplace arrangements.”

2. Vehicle (tailpipe) pollution standards

Vehicle pollution standards relate to the pollutants coming out of a vehicle tailpipe. These standards are primarily aimed at improving overall air quality in order to ‘protect human life’.

The earliest ones were introduced in California during the 1950s, with the California Air Resources Board (CARB) set-up to oversee them in 1967. Since then, California has generally set the world’s direction in vehicle pollution standards.

Whilst these pollutants do include some of the greenhouse gases as they can also damage human health: many others are included in these standards – such as nitrous oxides and fine particulates.

It’s also important to note that more stringent vehicle pollution standards now generally result in improved fuel economy (less fuel used = less pollutants overall) meaning vehicles designed to them are cheaper to run.

Sadly, Australia lags far behind all the other OECD countries in relation to vehicle pollution standards. Our current ones are based on the long-superseded European Euro 5 standard.

However, Euro 5 was replaced in Europe by Euro 6b back in 2014. (In fact, Euro 6b was replaced 6d back in 2017). Internationally through the UN, Euro 6b has been adopted as the world standard and as such is used by around 80% of the world, with 6d to be formally adopted very soon.

3. Greenhouse gas reduction targets

Setting overall vehicle greenhouse emission standards is often touted as a key step to reducing the contribution that transport makes to Australia’s overall CO2-e emissions.

(CO2-e being ‘carbon dioxide equivalent’ – meaning CO2 PLUS but the contribution of a selected set of other emitted gases that contribute to global warming. For vehicles, this particularly includes nitrogen oxides).

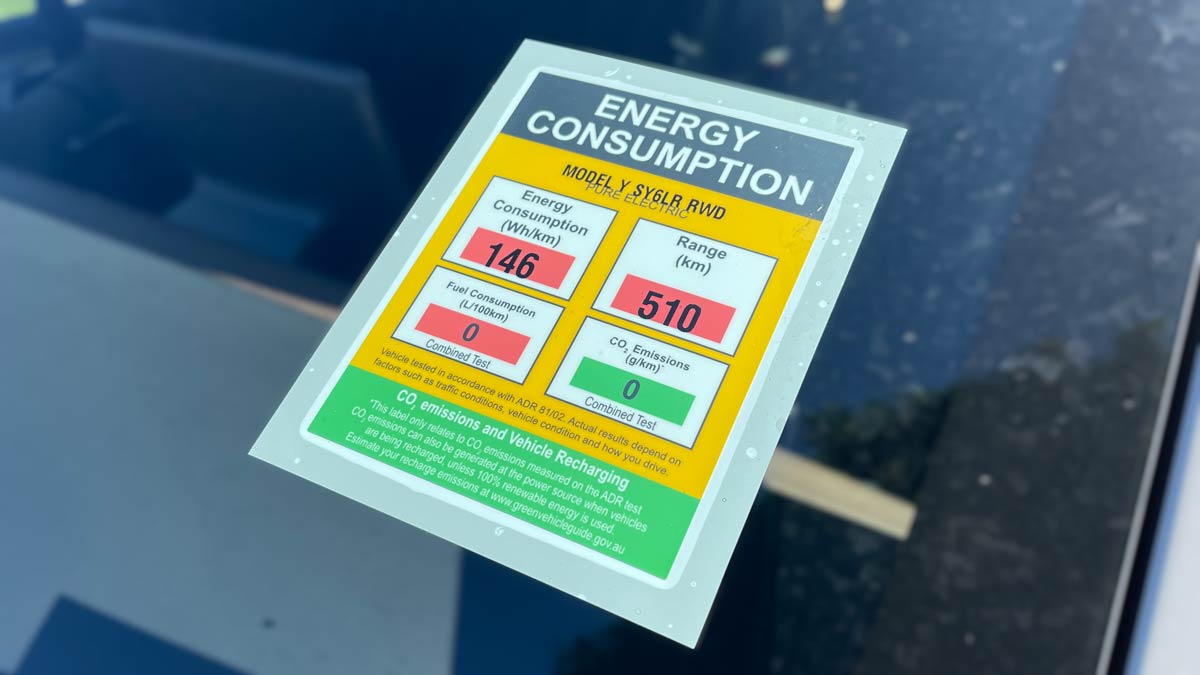

Many OECD countries mandate maximum vehicle greenhouse pollution standards, as measured through the Euro 6 emissions standard. In Europe, this is done through the proxy of grams CO2 emitted per km travelled (the CO2 g/km seen on windscreen stickers here) averaged for all vehicle models sold over a set period.

As health-harming pollutants like nitrogen oxides as well as greenhouse pollutants are reduced by Euro 6 (as well as the fuel quality that underpins it and the stringent testing requirements under 6d in particular) – this works reasonably well.

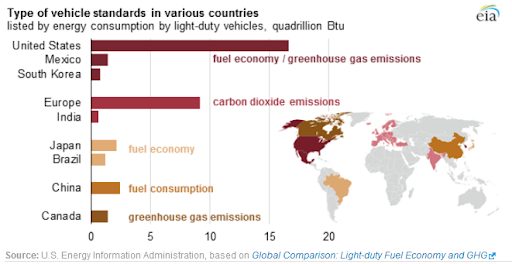

Different countries by the way use slightly different mechanisms to get to this point – some focus on fuel economy, some on fuel consumption and some on carbon dioxide emissions. The diagram below draws together these various methods:

Whichever mechanism specifics are chosen to enforce greenhouse gas reductions, the key point for these standards is they are mandated and come with ‘teeth’ – meaning that doing better than the standard results in credits, doing worse – fines.

It is worth noting here that as these mandated greenhouse gas limits are lowered (to meet ‘net zero’ by 2050), it becomes increasingly difficult for ICE vehicles to meet them. As a result, EVs (HEVs, PHEVs and eventually BEVs) become increasing favoured as the best way to meet the targets.

Australia currently has no such mandated limits, although there is a weak ‘voluntary’ scheme in place.

Also, as an aside: Tesla has for many years done quite well in selling their credits to other manufacturers – who then avoid being fined for exceeding their g/km limits.

So where to from here in Australia?

Currently, Australia is ‘on track’ to adopt better fuel quality and vehicle (tailpipe) pollution controls – but the previous Liberal government managed to put in place a very drawn-out process to get there.

Under their policy (which is still in place) – fuel quality is to be gradually improved to the currently existing world standard by 2027. At that point (and only at that point) is Australia move to Euro 6d. This by the way will put us well over a decade behind the rest of the world.

This lead-time was argued for by the then federal government in their submission to the Draft Regulation Impact Statement: Light Vehicle Emission Standards for Cleaner Air (by the Department of Infrastructure, Transport, Regional Development and Communications), in order to “provide refineries with certainty for major investment decisions and allows them to plan workplace arrangements.”

Worse still, this delay in introducing fuel quality and vehicle pollution standards means we currently won’t get many of the cleaner, more fuel efficient vehicle models offered overseas brought here before 2027. To quote further from that report:

“Several stakeholders advised the department that fuel saving technologies are often packaged with engines meeting Euro 6 or equivalent standards in larger markets.

“However, it still may not be commercially viable (or even possible) for manufacturers to offer these technologies on older Euro 5 engines for the Australian market. … Manufacturers have also expressed concerns that our older vehicle emissions standards are making it increasingly difficult to convince their global parent companies that next generation engine technologies should be allocated to the Australian market”.

Put simply: without action on fuel quality, Euro 6 cannot be implemented here. Without Euro 6 as the Australian default vehicle pollution standard, any attempt to introduce greenhouse gas (CO2-e) emission standards in any form will result in a less than world-standard exercise.

In fact, a standard based on our current use of Euro 5 will do nothing to encourage manufacturers to bring their most fuel-efficient ICE vehicles here – let alone give weight to the Australian arms of the various vehicle manufacturers to prioritise bringing greater numbers of EVs to our currently EV starved market.

In conclusion:

Adopting ‘fuel emissions standards’ here actually turns into a three-step process:

- fuel quality standard improvement to international levels;

- adoption of Euro 6 emissions standards (preferably 6d);

- mandatory vehicle CO2, CO2-e or similar emission standards that include credits and fines to ensure compliance, and thereby supporting the eventual transition to BEV from ICE.

Doing all of these together would enable vehicle manufacturers to treat our vehicle market the same as those in the lead of the EV transition. It would encourage manufacturers to both send their least polluting, most fuel efficient ICE vehicles here AND supply more BEVs to our market.

Anything else is likely to result in perverse outcomes that will encourage manufacturers to continue bringing higher polluting Euro 5 vehicles, more HEVs and PHEVs (which still include internal combustion engines) … and fewer BEVs.

Bryce Gaton is an expert on electric vehicles and contributor for The Driven and Renew Economy. He has been working in the EV sector since 2008 and is currently working as EV electrical safety trainer/supervisor for the University of Melbourne. He also provides support for the EV Transition to business, government and the public through his EV Transition consultancy EVchoice.