Plug-in hybrid electric vehicles (PHEVs) may seem like the best of both worlds—they can run on electricity but won’t strand drivers if there’s nowhere to charge. These cars and SUVs are basically an electric vehicle and a gasoline vehicle in one, with both powertrains and the ability to switch fuels.

The problem is that when drivers don’t plug in, a PHEV is just an extra-heavy gasoline car. As laid out in its proposed regulation for light- and medium-duty vehicles released on April 12, the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) now plans to do something about it.

To date, EPA has given PHEVs the benefit of the doubt both in consumer labeling and in regulation. In theory, drivers should rely more heavily on electricity the longer the electric range of a PHEV—they can go further before the battery runs out.

To estimate the electric drive share of a PHEV of any particular range, EPA has relied on a study published by the Society of Automotive Engineers (SAE). That paper modeled this relationship based on survey data on trip lengths and essentially assumed that drivers plug in to charge every night.

Well, they don’t. Last year, the ICCT (the International Council on Clean Transportation) published a study using real-world data showing that, on average, drivers rely much less on electricity—and more on gasoline—than EPA has assumed. It is clear in the real-world data that many PHEV drivers simply never plug in at all.

Why would a driver purchase a PHEV if they don’t plan to make use of electric drive? Well, in some cases, PHEVs can be cheaper than their non-plug-in equivalents when factoring in federal and state incentives.

The pre-Inflation Reduction Act version of the $7,500 EV tax credit was paid out in full for some PHEV models and some states levelled additional rebates on top of that, like California’s Clean Vehicles Rebate Program.

After raking in these incentives, some drivers apparently drive their PHEVs like gasoline cars. Many others plug in sometimes, but not as much as EPA had assumed.

The upshot is that EPA had been giving automakers too much credit for greenhouse gas (GHG) reductions from the PHEVs they sold.

EPA counts electric vehicles as zero-carbon in its vehicle regulations, and PHEVs as partially-zero carbon, based on their assumed electric drive share. In effect, EPA was undercounting the GHG emissions from the higher-than-expected gas guzzling of PHEVs.

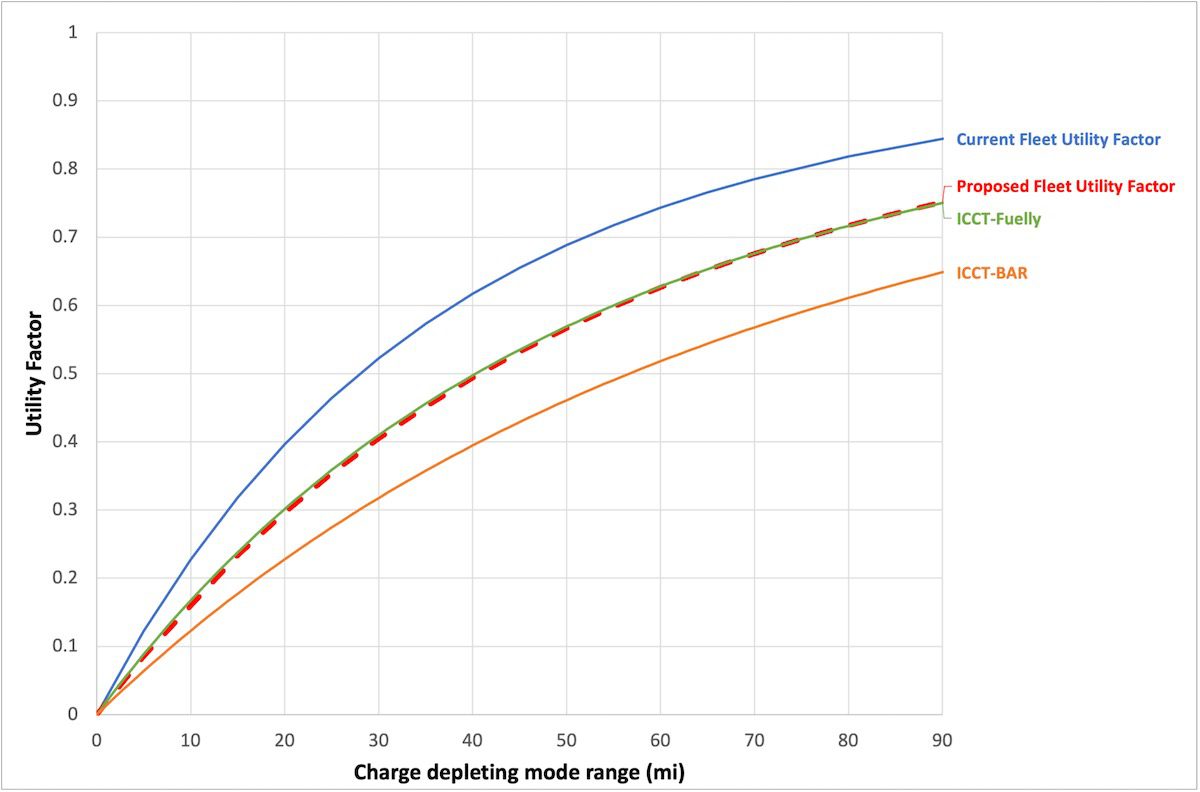

EPA is addressing that problem now by lowering their assumed PHEV electric drive share. The figure below shows EPA’s previously assumed drive share in blue and their proposed revision to that curve in red.

EPA’s proposed new curve is almost exactly the same as the one in our 2022 study, shown in green, which we derived from user-reported data in the Fuelly app. As a result, EPA’s estimates have moved closer to real-world usage. For example, a PHEV with a 35-mile electric range will be labeled as 45% zero-carbon instead of 57%.

This is a big improvement and brings EPA’s regulatory treatment of PHEVs much more in line with the real-world data, but we actually think the curve should be even lower.

The Fuelly data is reported by users who are using the app to track their fuel consumption. Naturally, this self-selected sample of PHEV drivers is likely to be skewed towards those concerned about their fuel consumption and, thus, more likely to plug in.

In our 2022 study, we looked at another, less biased dataset: on-board diagnostic data collected by the California Bureau of Automotive Repair (BAR) for PHEVs sold, used, or imported into the state. The BAR data is uploaded straight from vehicle computers and thus is not user-biased in any way other than representing only Californian vehicles.

That data curve, shown in orange in the figure, is significantly lower than EPA’s proposal and the Fuelly curve. Since this dataset includes drivers who are not concerned about their fuel consumption as well as those that are, it unsurprisingly shows even lower electric drive share—and higher gasoline consumption—than the Fuelly data.

It’s a positive step that EPA is undertaking efforts to stop the over-crediting of PHEVs in the proposed light-duty vehicle GHG standards. However, as the data supports, we think they could be doing even more to better reflect the real-world emissions of PHEVs .

First published at ICCT. Reproduced with permission.