Last weekend, the state of Victoria announced a collection of new 2025 and 2030 climate change targets. The state aims to reduce emissions by between 45 to 30%, by 2030 – something that was broadly welcomed, but also cautiously criticised, including by myself, as missing some key areas of short term action that could bring the state in line with more ambitious global climate goals.

One of the key elements of the Victorian government’s press release was one of the most contentious issues over the past few months. The state has now established a 50% by 2030 target for the sales of electric vehicles, in addition to a $3,000 subsidy payments for the purchase of electric vehicles.

That comes after a long-criticised policy to introduce road user charging for electric vehicles to ‘make up’ for revenue lost from the same tax applied to combustion engine vehicles through the purchase of fuels.

The question of whether this balance is right is complex. Any mode of transport – yes, that includes bicycles and walking – comes with some cost to maintain the surfaces, signals and other infrastructure. But the climate problem is unique, and deeply urgent, and some trade-offs will have to be made to rapidly rectify the threat of greenhouse gas emissions.

So is Victoria’s EV policy sufficient? And is it ambitious? It’s worth exploring, at least briefly.

What will happen in Victoria’s transport sector?

It’s surprisingly hard to find projections for emissions broken down into the state level in Australia. That makes assessing the ambition of new policies pretty difficult – we have no real baseline to judge them against.

However, one interesting conceptualisation of the future of EVs in Australia comes from the Integrated System Plan’s detailed assumptions. They are not forecasts, or modelling outputs – they are simply a load-bearing part of the structure of AEMO’s model used to explore various possible futures for the grid. As they were not the focus of the ISP, they aren’t a ‘dial’ twisted in the modelling exercise.

However, these assumptions are telling in and of themselves. They are based off two reports – one from the CSIRO, and one from Energeia. In their assumptions, Victoria leads the way in all scenarios. Looking at the middle range scenario, Victoria’s total electricity demand is 2% electric vehicles by the year 2030:

It is an interesting outcome that suggests, at the very least, existing knowledge on Victoria’s capacity to absorb electric vehicles is relatively strong.

The Energeia modelling suggests that, for Australia, there’s a chance EVs could comprise up to 30% of the total annual sales of vehicles. That’s roughly in line with the 26% of market share in the 2020 federal government projections.

Bloomberg are slightly more pessimistic, suggesting recently that it’ll be around 18% by 2030.

Whatever the figure, Victoria’s 50% by 2030 is pretty clearly above the national average. And when it comes to transport, Australia as a whole is really starting at rock bottom.

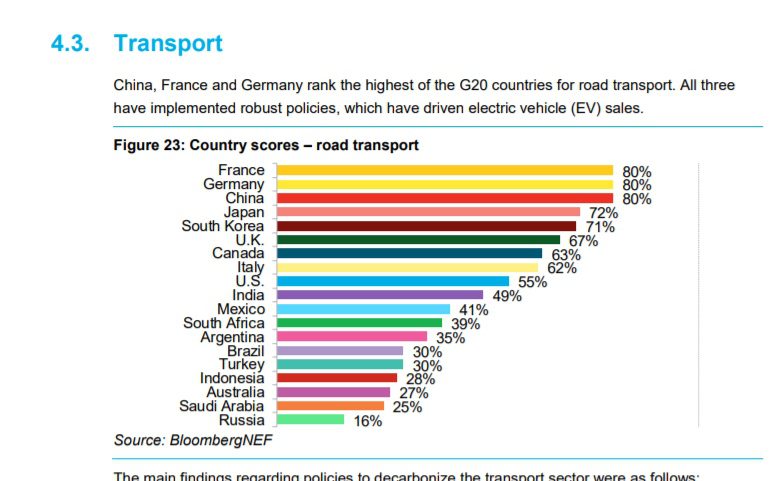

Earlier this year, Bloomberg New Energy Finance ranked Australia third last – beating Russia and Saudi Arabia (just) in terms of scores for road transport emissions reductions policies.

For some time, transport has been a key component of Victoria’s emissions footprint. But as I found recently from newly released state-level emissions data, per-capita figures for transport in Victoria are falling noticeably lower:

But, emissions from transport in Victoria are also rising as a share of total emissions in the state, as the power sector decarbonises rapidly:

Despite there being very little baseline to compare Victoria to, it’s relatively clear that the EV sales target they have set is relatively ambitious.

At the very least, this proportion of new sales by 2030 will begin a slow decline in the state’s rising transport emissions, and accelerate the total decline in emissions that has been driven by change in the electricity and land use sectors to date.

However, it’s still not clear whether one-off incentives will get to that target, or whether road user charging will serve as a brake on these ambitions.

Ketan Joshi has been at the forefront of clean energy for eight years, starting out as a data analyst working in wind energy, and expanding that knowledge base to community engagement, climate science and new energy technology. He writes for The Driven’s parent site, RenewEconomy, and has also written for the Guardian, The Monthly, ABC News and has penned several hundred blog posts digging into climate and energy issues, building a position as a respected and analytical energy commentator in Australia. He’s spoken at the Ethics Centre IQ2 debates on the need for urgent decarbonisation, he’s served as an subject matter expert on national television, and has a wide following on social media around energy and climate.