Having lived in Oslo for a full year now, I am well and truly used to walking around the city among electric vehicles. They’re extremely common; peering outside my window right now I can see a BMW i3, a shiny new Nissan Leaf, and a Tesla Model 3. They’re all charged up using the extremely-low-emissions Norwegian electrical grid, almost entirely hydro power with some wind and gas generation.

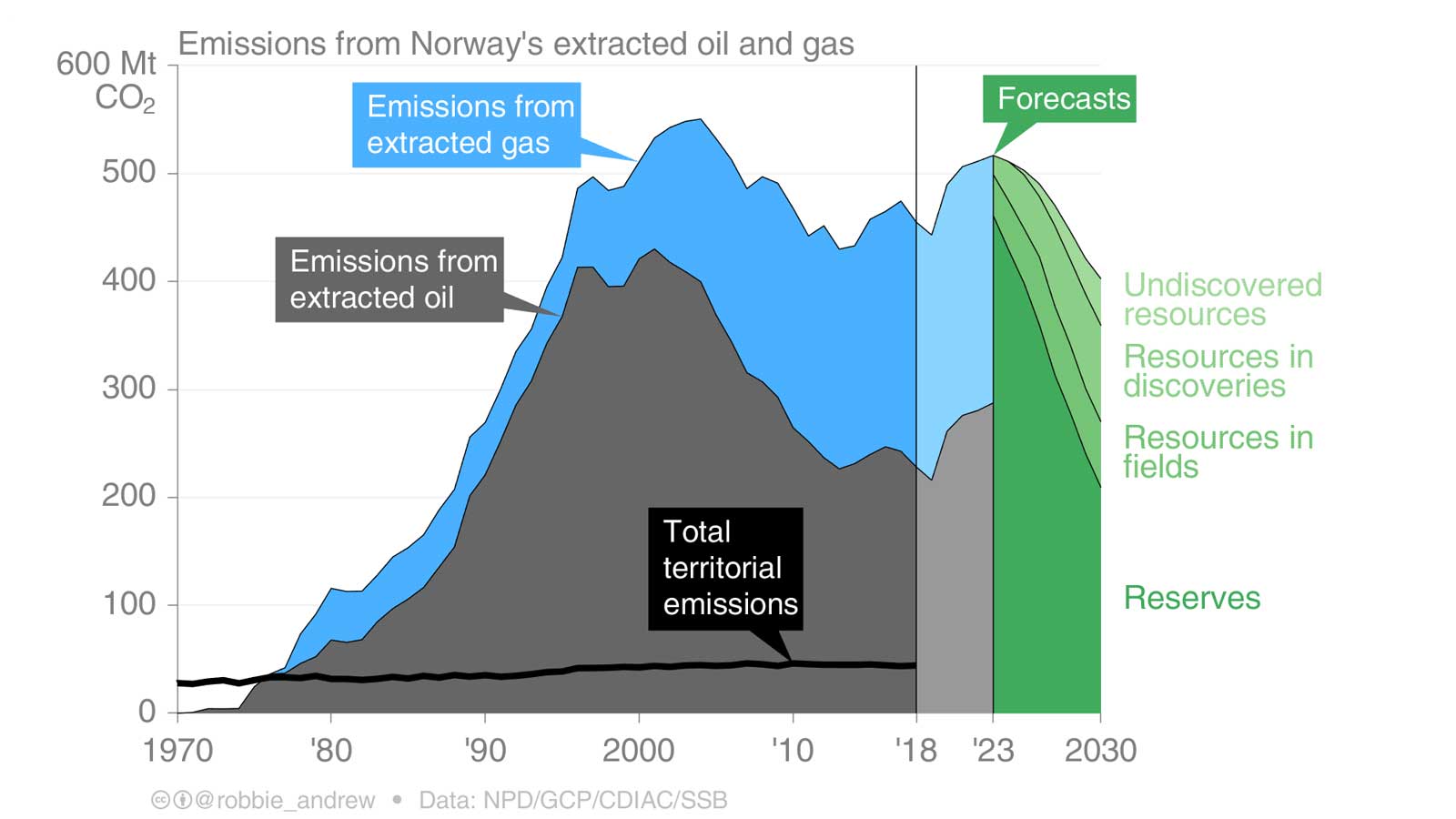

Norway is also a global leader in the extraction and sale of fossil fuels. Mostly oil, with some gas, the country’s leaders plan to continue exploring for, extracting and selling these fossil fuels well into the future. And the emissions that stem from these activities once these fuels are burned massively outweigh emissions from within the borders of Norway:

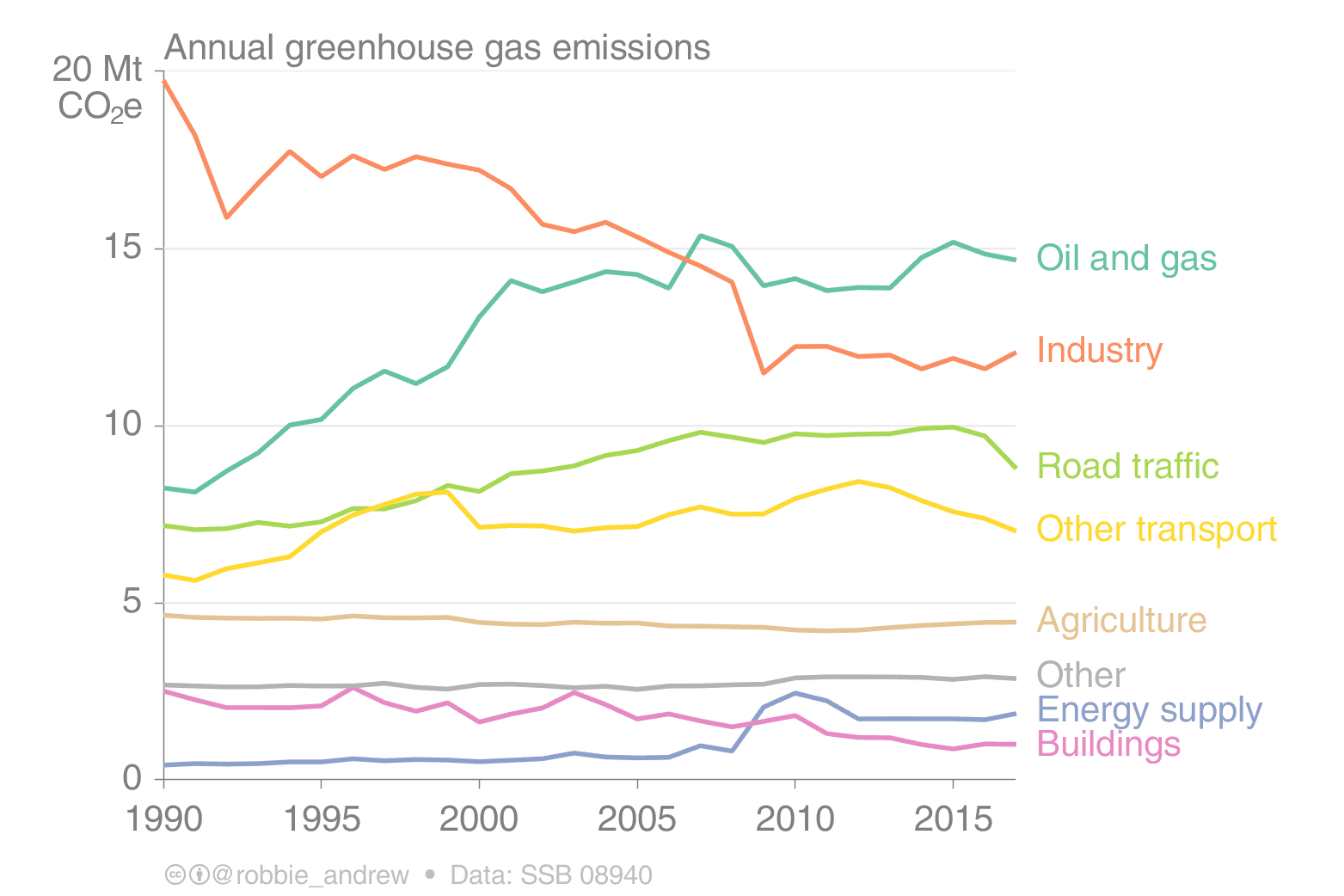

The problem is double-barreled – the oil and gas extraction industry also increases emissions within the country, because these extraction processes are themselves emissions intensive, even before any fossil fuels are combusted in the bellies of combustion engine vehicles:

These are two conflicting stories. Movement here in Oslo, and in Norway in general, is among the cleanest in the world. But the country still relies heavily on selling fossil fuels, with a big emissions impact both domestically and overseas.

EVs are set for a global rise – but it needs to be quicker

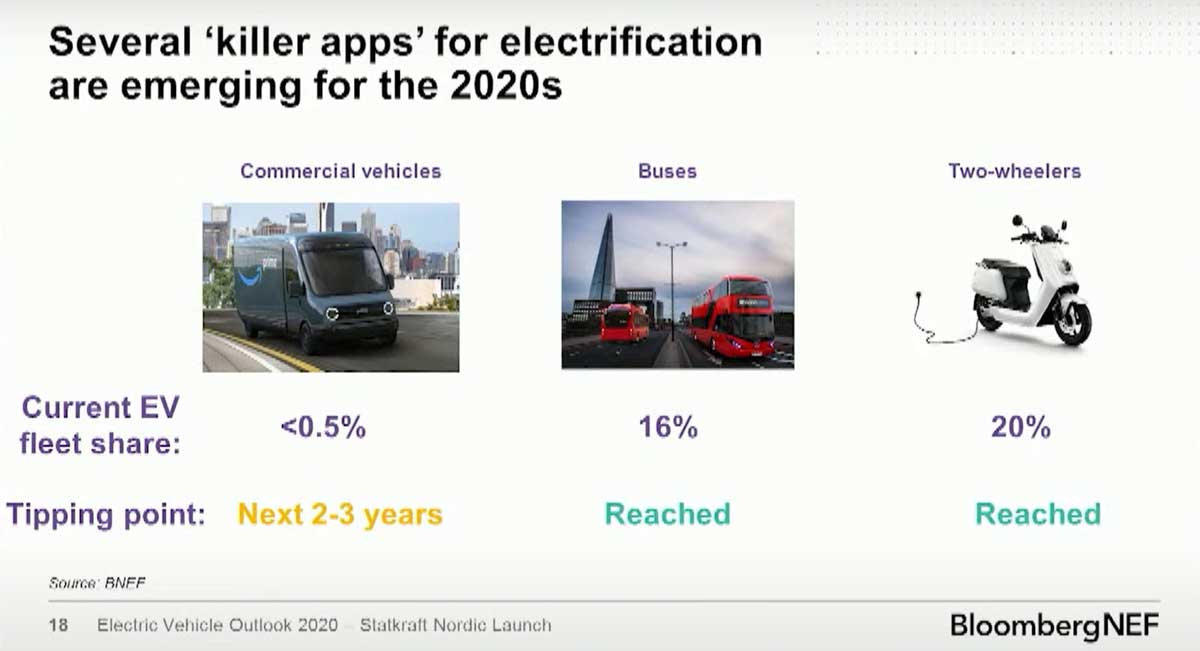

Recently, Norwegian hydro giant Statkraft hosted the Nordic launch of Bloomberg New Energy Finance (BNEF)’s ‘Electric Vehicle Outlook (EVO) 2020’, summarising both the impacts of COVID-19 on transport and the near-future prospects for transition in transport.

The core message of BNEF’s EVO is that peak combustion came and went, and we barely noticed.

“Sales of internal combustion passenger vehicles peaked in 2017 and are in permanent decline”, the report states. COVID-19 is predicted to impact all vehicle sales, but “EV sales will drop less, and come back faster”, said BNEF’s Colin McKerracher, the lead author on the report.

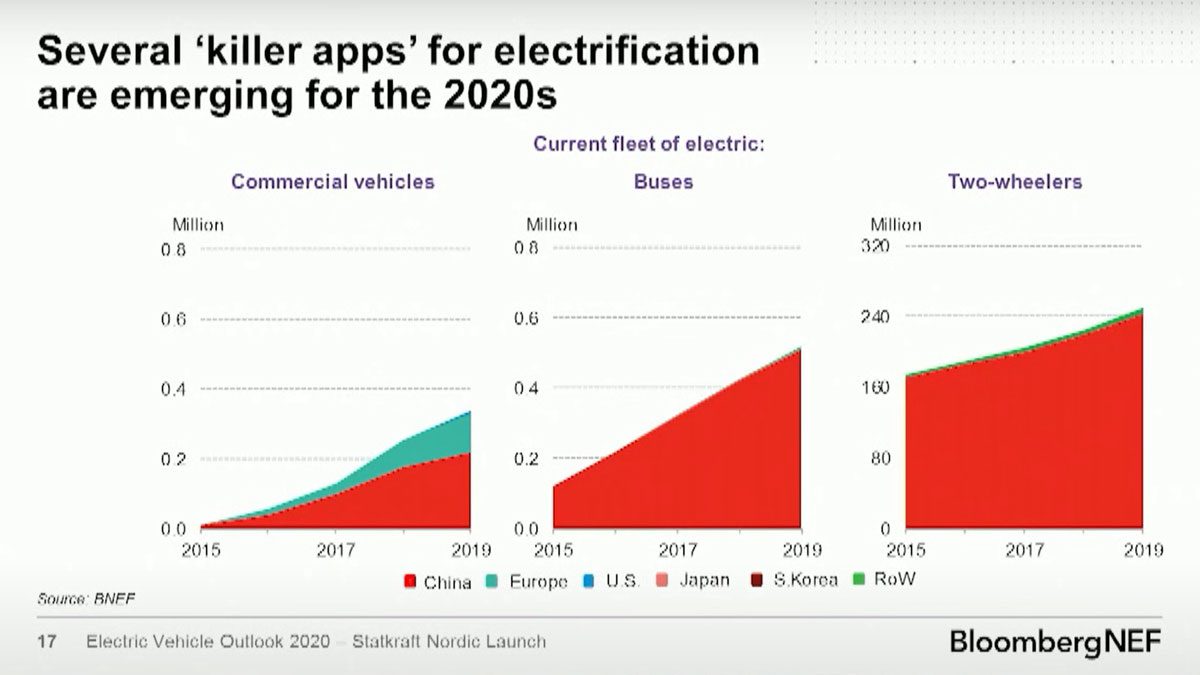

EVs will reach price parity in the mid 2020s (a long-held prediction that may be surpassed well prior). China and Europe are pulling ahead of the US, both with massive contributions to decarbonisation of transport. Already, 16% of the world’s bus fleet has been converted to electricity – that is almost entirely due to China.

BNEF – true to form – is bullishly optimistic about change. “It goes slow and then it goes fast”, said McKerracher, of Norway’s successful government incentivisation of electric vehicles, resulting in a rise to nearly 60% of new sales fully electric by the end of 2019.

Pulling all the projection together, there is a simple and fascinating conclusion. “Oil demand from passenger vehicles has already peaked in our forecast was another surprising conclusion, perhaps a controversial one”, said McKerracher.

They project that overall oil demand for all road transport (including things like large trucks) is set to peak in 2031. And pointing out that all of these trends are insufficient to climate targets that keep Earth within less dangerous levels of warming, McKerracher seems to be hinting the reality might be even more dire for oil.

“It’s a major task for all of us here to make this go even faster and prove Bloomberg New Energy Finance wrong”, said Marius Holm of Norwegian climate and energy advocacy group Zero, on the webinar’s panel.

It is an optimistic vision for cleaner, better transport around the world. How is it received in a country that relies heavily on selling oil?

What about oil?

Norway’s contradiction is a fascinating one, and it came through on the panel of speakers in the webinar. It is a country that is a world leader in the development of electric technology that, as BNEF’s 2020 EVO shows, is directly contributing to the global decline of oil – one of the country’s biggest exports and the key source of its immense wealth.

“What we’ve done in Norway is, by all means, a gigantic paradox”, said Tina Bru, from Norway’s Ministry of Petroleum and Energy. Norway’s EV policy is “a clear policy removing the need for our main export product, which is oil and gas. But it is the right thing to do”.

But in defending a significant tax breaks granted to Norway’s oil and gas companies as part of its COVID-19 response, Bru said “this is our main technology industry and represents thousands of jobs”.

Statkraft’s CEO, Christian Rynning-Tønnesen, baulks at the idea of disincentivising oil and gas too, preferring a demand-reduction approach. “I don’t think the change will come from lack of oil and gas, or lack coal for that matter”, he said.

“Most oil fields, they have a decline rate that is of such amount that we still need new oil supply in the world to replace all the old oil fields. It’s possible to have a profitable oil and gas business as well”, though Rynning-Tønnesen adds that he too hopes BNEF’s forecasts will be surpassed.

The point is refuted by politician Kari Elisabeth Kaski. “Should we be planning for and subsidising starting up new oil production in the Barents Sea?”, she asked.

It is a confusing tension; to be simultaneously pushing in one direction on oil demand with one hand and in the opposite direction with the other hand. Both McKerracher and BNEF’s Seb Henbest point out Norway’s policies in particular are highly influential on the world’s EV market.

The overarching message is that even if oil is doomed, it must be slowly doomed. One particularly telling article published on the website of the Norwegian Government’s Norwegian Petroleum Directorate (NPD) paints a picture of a world where oil production were to suddenly cease, replete with cartoons of a return to ancient times:

“Our view is that Norway and Equinor will continue to be involved with oil and gas for many decades to come even if we move towards the climate goals” says Equinor CEO Eirik Wærness, on the page.

It is certainly a time when nobody feels relief knowing that society depends on a fuel and technology we know causes harm to human society, so the article is both strange and telling in its insistence that fossil fuels will be around for many decades, whether we like it or not.

If the past decade is anything to go by, even the optimistic forecasts of an electric revolution are too pessimistic. That’s going to test the arguments being put forth for Norway’s continued heavy investment in the extraction and sale of oil, instead of an immediate, controlled transition away from that and towards less-exposed industries.

Paradoxes never last; one side will win out. First, change comes slow, then it comes fast. What happens when the world moves from ‘slow’ to ‘fast’ on the electrification of transport, and demand for oil collapses? Norway will be the first to know the answer.

Ketan Joshi has been at the forefront of clean energy for eight years, starting out as a data analyst working in wind energy, and expanding that knowledge base to community engagement, climate science and new energy technology. He writes for The Driven’s parent site, RenewEconomy, and has also written for the Guardian, The Monthly, ABC News and has penned several hundred blog posts digging into climate and energy issues, building a position as a respected and analytical energy commentator in Australia. He’s spoken at the Ethics Centre IQ2 debates on the need for urgent decarbonisation, he’s served as an subject matter expert on national television, and has a wide following on social media around energy and climate.