As arguments rage in Australia over the electric vehicle policy unveiled by Labor last week – aiming for a 50 per cent share of electric vehicles in new car sales by 2030 – over the Tasman in New Zealand the government is expected to be even more ambitious.

Analysts there are expecting New Zealand to reach 100 per cent of new vehicles by 2030, as part of a plan to ensure that 90 per cent of the entire fleet, if not 100 per cent, is electric by 2050.

“Our base case assumption is that EVs will achieve 100% penetration of new light fleet imports by 2030 and 100% of used imports by 2035,” Deutsche Bank analysts said in a recent report.

“This leads to an expectation for 15% of the light fleet to be electric by 2030, climbing to 53% by 2040 and 90% by 2050.”

This is in line with local Productivity Commission, which last year reacted to the country’s soaring emissions by saying New Zealand “must stop burning fossil fuels”, and switch quickly to electricity for transport and heating.

“This means a rapid and comprehensive switch of the light vehicle fleet to electric vehicles (EVs) and other very low-emissions vehicles, and a switch away from fossil fuels in providing process heat for industry,” it said in its report.

And it came to a similar conclusion to Deutsche Bank analysts: “To electrify the bulk of the light vehicle fleet by 2050, nearly all newly registered vehicles (including used imports) would need to be electric by the early 2030s,” it said.

And it came to a similar conclusion to Deutsche Bank analysts: “To electrify the bulk of the light vehicle fleet by 2050, nearly all newly registered vehicles (including used imports) would need to be electric by the early 2030s,” it said.

The Productivity Commission recommended a range of options to encourage EVs, including a “feebate” scheme, in which importers would either pay a fee or receive a rebate, depending on the emissions intensity of the imported vehicle.

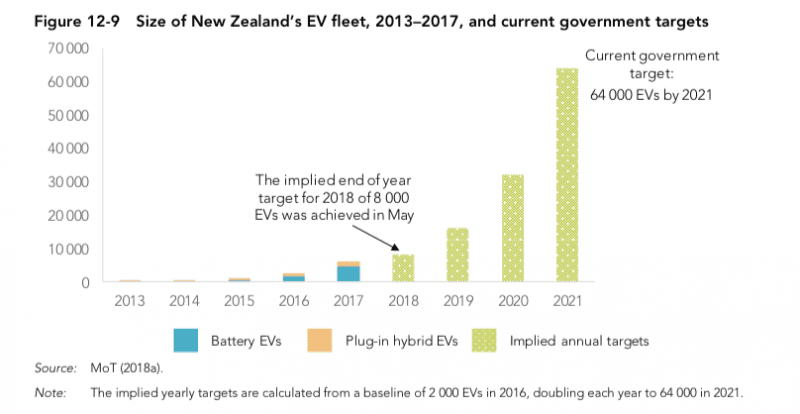

Currently, the country has a target of 64,000 EVs by 2021, which it is supporting by exempting EVs from road user charges (worth around $NZ600 a year). You can check out monthly sales here.

The Productivity Commission also recommends funding to help fill gaps in the charging network that are commercially unviable for the private sector.

A similar approach is recommended in Australia by Labor, which is putting most of its emphasis on the EV transition to fleets, and by offering accelerated depreciation for fleet operators for EVs they purchase.

New Zealand climate change minister James Shaw, the co-leader of the Greens and who drives an electric car (a Hyundai Ioniq), has been promising to unveil a detailed climate change strategy, and the EV component, since last October.

His options include mandating a rapid shift to electric for the government car fleet, and following Norway’s example in making electric vehicle purchases exempt from GST. EVs now account for more than 50 per cent of new vehicle sales in Norway.

He may have to add extra incentives to meet the 2021 target of 64,000 vehicles, which Deutsche analysts say will need to see a trebling in the current rate of additions to meet.

Pressure to act will intensify following new Greenhouse Gas Inventory figures that showed New Zealand’s gross emissions jumped 2.2 per cent between 2016 and 2017, and brought the increase in emissions between 1990 and 2017 to 23.1 per cent.

Road transport is one of the biggest offenders: Emissions from road transport climbed by 6 per cent in the last year.

This is despite sales of electric cars in New Zealand rising progressively and being considerably higher than Australia, although most are second hand EVs imported from Japan.

One of the reasons is that New Zealand, according to the Productivity Commission has become a dumping ground for dirty cars because of its lack of fuel emissions standards – the same issue that afflicts Australia.

Giles Parkinson is founder and editor of The Driven, and also edits and founded the Renew Economy and One Step Off The Grid web sites. He has been a journalist for nearly 40 years, is a former business and deputy editor of the Australian Financial Review, and owns a Tesla Model 3.