The downturn in global new car sales started in 2017, steepened in 2020 thanks to Covid, and even though it has rebounded in many markets in 2021, it is still below the levels of 2019.

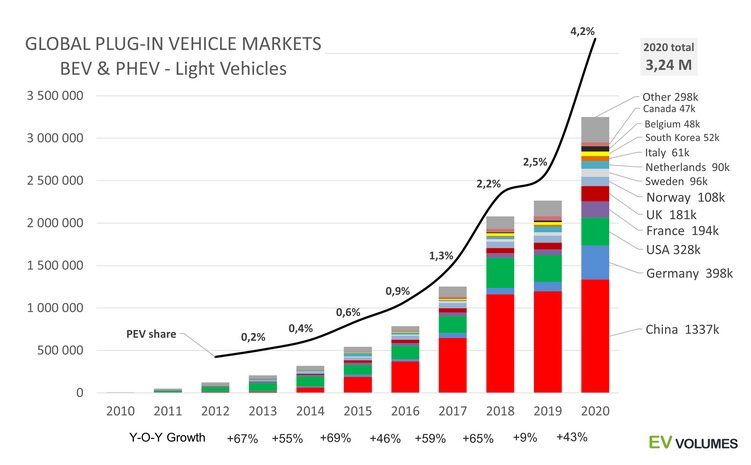

Worldwide new plug-in electric vehicle sales were up over 43% year-on-year, from 2.26 million in 2019 to 3.24 million in 2020. That delivered plug-in electric vehicle sales – both full battery electric and plug in hybrids – a 4.2 per cent share of the global new car market in 2020.

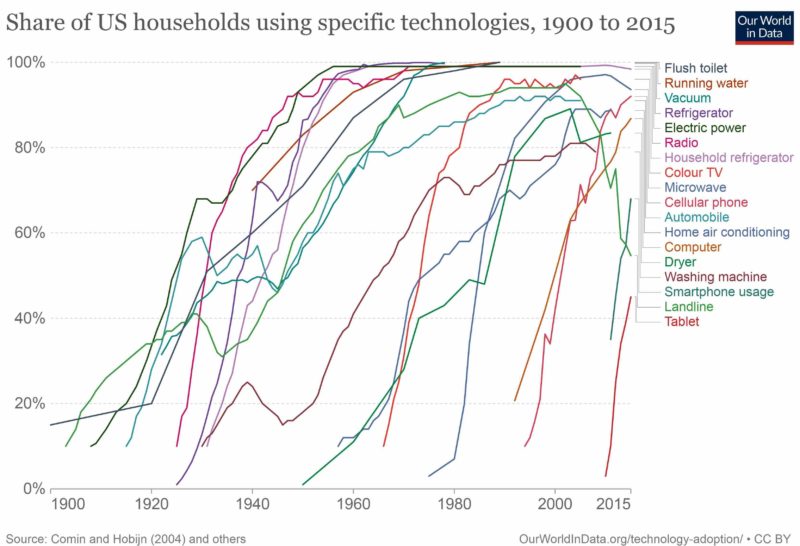

Looking closer for a moment at the trend shown in figure 1 (above), EV uptake appears to be following the typical uptake curve of all of our most ubiquitous current technologies, as shown in figure 2 (below)

If EVs are following this path, it may not be long before the ICE (Internal Combustion Engine) vehicle goes the way of (and as quickly as) the horse and carriage (figure 3). This would be far faster than current industry predictions of 30 to 50% new EV sales by 2030.

Source: Ourworldindata.org/technology-adoption/

Interestingly, not all countries are at the same point of the EV uptake curve. Norway (with 2025 legislated as their date to end all new non-EV sales) is nearing the top already – with monthly PEV sales in July this year hitting 84.7% and full battery EVs alone making up 61.4%.

Many nearby EU countries are not all that far behind. Sweden hit 37.6% PEV sales in July, Germany 23.5% and the UK 17.1%.

Another interesting sign-of-the-times is the decline of the diesel engine passenger vehicle. For example, in July this year UK new diesel passenger vehicle sales fell to 7.1% (from 16.5% a year earlier) – and BEV passenger vehicle sales (at 9%) exceeded sales of diesel vehicles for the first time.

Meanwhile, Australian PEV sales have also seen a ‘blistering’ rise … from 0.57% overall for 2020 to almost 2% in July 2021 monthly sales.

Given the emerging EV trend elsewhere – it seems very head-in-the-sand of our national government to be pumping billions into subsidising oil refineries whilst avoiding any form of EV Transition recognition or support.

Harking back to the point I began this article with, regarding the ongoing fall in new ICE vehicle sales that began back in 2017, it’s interesting to note that there has been a surprising rise in used car prices – first with recently second-hand vehicles and more recently, older ones.

Traditional automotive pundits have connected the fall in new sales and the rise in used prices to a combination of reduced availability of new cars due to the chip crisis (odd, since increasing used car prices began well before Covid), tightening economic conditions causing people to delay or avoid new car purchases, and a related increased demand for used cars causing decreased availability of them creating higher used car prices. (They also never seem to include the countervailing rise of new EV sales in their discussions ….)

The Osborne Effect at play?

I would like to suggest an alternative explanation: that all three trends taken together are an example of ‘The Osborne Effect’.

The term was coined after the collapse of the Osborne Computer Company, when customers stopped buying the company’s first computer product after the premature announcement of its successor before it was available.

The Osborne Effect is defined as “a social phenomenon of customers cancelling or deferring orders for the current soon-to-be-obsolete product as an unexpected drawback of a company’s announcing a future product prematurely” (Wikipedia).

New York: 5th Avenue, April 1900 and Easter 1913. Circled: sole petrol car in 1900 and sole horse and carriage in 1913.

Sources: US national archives/Wikipedia and George Bantham Bain Collection.

You can easily apply this to EVs: cars that can do everything an ICE vehicle can have been around ever since the Tesla Model S arrived.

Given its capabilities, and the move to mass production heralded by the announcement of the Model 3 (which coincidentally went on sale in mid-2017) – I would contend that new ICE car purchasing has become ever more delayed as people await the arrival of mass market EVs from the rest of the manufacturers.

This is because EVs are seen as the better (and inevitable) vehicle technology that is close to being readily available. Especially so as EV prices are generally expected to soon be comparable to ICE ones.

In an effort to seemingly slow Tesla sales, the major manufacturers have effectively been feeding the Osborne Effect by constantly announcing coming EV models – but delaying their introduction or manufacturing them in limited numbers.

In that light, falling new ICE sales and rising second-hand sales (and therefore prices) make sense. As the EV versus ICE price parity point draws closer, buying an ICE vehicle makes less and less sense as it is seen likely it will quickly become obsolete, with a resale price to match.

Instead, hanging onto the existing ICE vehicle, or if necessary buying a second-hand ICE to ‘tide one over’ would be the more sensible move.

This could also go some way to explaining why ever older second-hand vehicles are now becoming popular buys – acceptable EV pricing and availability are seen as getting closer and the temporary ICE vehicle is needed for less time.

To me, this is a better explanation for, and potential connection of, the three trends than that offered by the traditional explanations.

I would also suggest the automakers themselves are quietly acknowledging an EV induced Osborne Effect, for they are now starting to bolt for the EV door.

GM, Ford, Volvo and VW group have all set dates ranging from 2025 – 2035 for the cessation of ICE vehicle production, whilst others are setting targets for the electrification of their new fleet offerings.

Examples also include Stellantis* (the world’s fourth largest auto group) announcing that by 2030 they plan to have PEV sales of over 70% in Europe and over 40% in the US and the Jaguar Land Rover group (JLR) moving the Jaguar brand to full EV by 2025.

Even Toyota (the stand-out laggard on full-battery EVs, despite taking the early hybrid lead with the Prius way back in 1997) has recently announced the dedicated all-electric vehicle e-TNGA platform and stated their intention to release 15 new battery-electric vehicles by 2025.

Meanwhile, the market leader in EVs (Tesla) is doubling its 2020 output of around 500,000 vehicles to reach 1 million this year …. with two more Gigafactories nearing completion and expected to begin production late this year or early next. Plus there are growing rumours of a new ‘mass market’ small Tesla in the wings.

Tesla has also recently inked a deal with BHP to provide nickel from the Nickel West mine in WA that includes plans to make the battery supply chain more sustainable.

Given Tesla’s dominance in EV tech, rapidly growing production capacity and general commitment to sustainability – it is hardly surprising that Tesla is around eight times the current value of GM … and thirteen times that of Ford.

So over to you – the reader. Are we seeing the start of an Osborne Effect triggered by Tesla and accidentally reinforced by the majors?

Will the EV Transition happen much faster than the industry predicted levels of 30 to 50% new EV sales by 2030 – instead hitting 80% or more of new car sales like Norway is now?

Will the vast majority of models in showrooms soon be electric powered simply because no-one will buy ICE ones anymore? … And will ‘electric cars’ soon be so ubiquitous that we drop word ‘electric’ from their description?

* Note: Stellantis: the world’s fourth largest auto group. Their stable of brands include Peugeot, Citroen, Opel, Vauxhall, Jeep, Fiat, Chrysler, Ram, Maserati and Alfa Romeo.

Bryce Gaton is an expert on electric vehicles and contributor for The Driven and Renew Economy. He has been working in the EV sector since 2008 and is currently working as EV electrical safety trainer/supervisor for the University of Melbourne. He also provides support for the EV Transition to business, government and the public through his EV Transition consultancy EVchoice.