BlackBerry is best known as the company that the Apple iPhone all but destroyed. But since it stopped making smartphones in 2016, the Canadian firm has quietly turned its attentions to another area: car operating systems.

It has quickly become a market leader. BlackBerry says its QNX operating system is already used in 175 million vehicles worldwide, and demand for its products is only growing as cars increasingly become computers on wheels, and amid the anticipated shift to electric and autonomous vehicle.

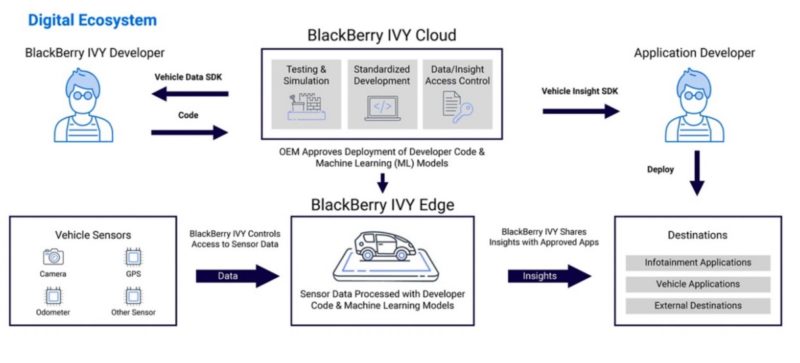

But perhaps its most interesting development is a new software platform called BlackBerry IVY. Launched in March this year as a joint venture with Amazon’s cloud computing subsidiary AWS, BlackBerry IVY aims to go mainstream with the sort of powerful, integrated, highly-connected systems we associate with the likes of Tesla.

BlackBerry IVY can take data from all of the vehicle’s sensors – cameras, heat sensors, speedometre, radar, etc. – and use that data for any number of purposes, from improving immediate car performance and aiding the driver, to informing higher level insights to drive business strategy.

This is something Tesla is already leading the industry in. Its ability to harvest data and analyse it in real time gives it a significant edge over less connected, stupider (for want of a better word) cars – and has allowed it to do novel things like sell highly-tailored insurance products to its customers.

It allows the car to continuously update and improve, using all the benefits of connectivity and cloud-based computer power to do so.

But where Tesla – like BlackBerry’s one-time rival Apple – uses a “closed platform”, BlackBerry IVY aims to be available to all carmakers. In that sense it could be likened to Google’s open source Android operating system, which is used by most smartphones that aren’t made by Apple.

“You can think about Tesla’s platform as a closed platform,” says Sarah Tatsis, senior vice president of BlackBerry’s Advanced Technology Development Labs. “But what we’re creating is an open platform, or a platform that can be standardised across OEMs [original equipment manufacturers – i.e. carmakers] and across a mix of models.”

The idea, she says, is to open the platform to a “really broad set of developers”. IVY has not yet been released, but Tatsis says the market will only grow, and the company is in talks with a number of major carmakers who are interested in using the platform.

“I think over the next number of years most of the OEMs have a strategy around releasing connected vehicles and EVs that are connected as well. So I think we will see more and more of that. We’ll see a transition to most of the cars that are rolling off the lot that are connected and have additional capabilities in them.”

She says at the moment, BlackBerry’s main competitors are the OEMs themselves. But by offering car makers an open-source platform, she says it will save theminvesting huge sums of money in a line of business in which they are not specialists, allowing them to concentrate on what they do best.

It’s a vision that fits into the broader narrative of 5G, Internet of Things, and smart cities – a world in which the internet becomes a mutant of its former self, and everyday appliances, from fridges to lawnmowers to traffic lights, are connected to the internet and can communicate with each other.

In this world, much of the computing activity takes place close to the site – at the “edge” of the network rather than sending the data to the cloud – massively increasing efficiency and reducing latency, but also posing new cybersecurity risks.

One major selling point BlackBerry will bring is its expertise in cybersecurity. Its main other line of business now is securing mobile devices such as phones and laptops, minimising their vulnerability to cyberattacks.

As cars become more connected, they will inevitably become more vulnerable to cyberattacks, and BlackBerry will use its existing expertise in this area to keep the information secure.

The key, says Tatsis, is securing “endpoints” such as cameras and other sensors, to make sure the information they are collecting and sharing is legitimate. Connected cars, she says, are a highly complex collections of endpoints, or “endpoints of endpoints”.

“A car is a collection of a lot of different components, including many different sensors,” she says.

She gives the example of securing the data coming from a camera, and “making sure that that’s legit and stays legit so that nobody has hacked that camera feed and it’s not giving incorrect signals”. This sort of cybersecurity must cover every sensor in the car.

The technology will also allow cars to communicate with smart devices outside the car, such as other cars or traffic lights.

“The vehicle itself has a lot of information in it, but it could also be communicating directly with the traffic signal, for instance. Or we could think about things like kind of the connection of home IoT,” she says.

“Things like EV charging stations would be connected. So your car could pay for itself from its wallet for EV charging.”

How will all this data be used? Specific to EVs, Tatsis says it could be used to help drivers modify their driving habits to extend the range of the battery, and more generally it could be used to provide much more sohpisticated real-time information on traffic congestion. It could also be used to communicate with EV chargers.

But, as with 5G and the Internet of Things more broadly, many of the uses and benefits will depend upon innovations by the third party application developers.

Tatsis says the key is to “normalise” data across all makes and models to “really enable the development of a broader developer ecosystem”.

James Fernyhough is a reporter at RenewEconomy and The Driven. He has worked at The Australian Financial Review and the Financial Times, and is interested in all things related to climate change and the transition to a low-carbon economy.