Last week marked the 10th anniversary of the initial public offering of electric vehicle maker Tesla. And CEO Elon Musk and other investors had 324 billion reasons to celebrate: $324 bilion was market value of Tesla (in Australian dollars) at the end of the week.

It’s a phenomenal result by any means. Tesla hit the boards 10 years ago with a value of $1.7 billion, and since then has delivered an average annual return on that investment of 45 per cent.

In 2019, Tesla made 365,000 electric cars, a fine achievement. Toyota produced nearly nine million vehicles. Yet the market is judging Tesla to be the most valuable car company in the world, with a value of $890,000 for every car it made last year.

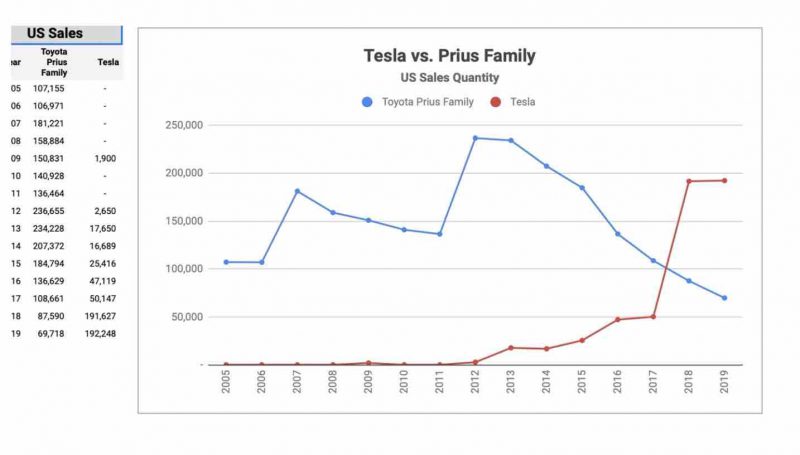

It’s a market value that seems barely believable by any conventional measure. But this is not about the past, or even the present, but the future. And this graph perhaps sums up the situation best.

It’s the story of sales of the Toyota Prius and Tesla EVs in the US. It is significant because it tells of two different strategies – one firmly on the future with no concern about legacy assets, and other with an eye to the past and a determination not to rock the boat, or its business model; and another strategy with the focus firmly on the future, and no legacy distractions.

Toyota won’t die because the Prius has passed it used by date. And hybrids continue to prove to be enormously popular, more so than Toyota ever expected. In the last year, more than 60 per cent of sales of popular models such as the RAV4 and the Camry have been the hybrid versions.

But this is the modern equivalent of the fax machine. Hybrids are easy and convenient, customers get to feel like they are saving money, and lowering emissions, but the company gets to keep its profits, and protect its business model.

But, like the fax machine, it’s not the answer, it’s just a stepping stone towards more fundamental change. Hybrids, according to Toyota’s own calculations, deliver maybe a 30 per cent saving in petrol and emissions.

That’s neat, but it’s not enough to meet climate goals, and EVs will be vastly superior. And when EVs reach cost parity, and the joy of driving them spreads through the population, then the stampede towards electric will be unstoppable.

The latest data tells the story. Despite the global slowdown in new car sales caused by the Covid-19 pandemic, sales of plug ins and full electrics are going up, and grabbing a greater market share. It’s the same story in Germany, and Australia, and nearly every other country. And surveys show that consumers want an EV to be their next vehicle, if the price is right.

So much so, some futurists such as Professor Ray Wills, head of Future Smart Strategies, an adjunct professors at UWA, and director of utility Horizon Power, are putting out some stunning forecasts about the pace of transition to electric vehicles.

Take this from last week – a prediction from Wills that by 2025, when EVs have well and truly reached cost parity, fossil fuel car sales will be all but over (including hybrids). The recent ending of fossil fuel car production at VW’s Zwickau plant is a taste of what’s to come.

“All major car makers have at least one model of electric vehicle, and have factories able to be retooled to produce electric cars rather than ICE cars,” Wills says. “Once traditional manufacturers get on with it and retool, the arrival of greater volumes of more affordable EVs will carry the day.

And that take us back to the market valuations of Tesla, Toyota, the other big car manufacturers and big oil. Investors are interested in recent events, and current profits, but they are more obsessed with what the future holds, and they have voted with their feet.

The highly respected Morgan Stanley analyst Adam Jonas recently noted that Tesla has reached its valuation despite EV penetration being shy of 1 per cent in the US market and roughly 2% globally.

He also noted that if the same multiples on EV production – present and future – that are ascribed to Tesla were to be applied to GM, then that company would be worth around $US100 billion.

The fact that it is not (current market value of GM is $US36 billion) suggests either that the market isn’t looking, or if it is, it is applying a negative value of its petrol and diesel fleet of minus $US60 billon.

The same thing is happening in different ways in Big Oil, a critical part of the Big Auto story because it provide the fuel that the petrol and diesel cars need to burn. While investors in Big Auto are voting with their feet, directors in Big Oil have one eye on their fiduciary duties.

Big Oil has enjoyed phenomenal market value over recent decades, and because of that access to whatever capital it needs, largely due to the assumed value of resources that it has not yet extracted.

The value of big miners are similarly judged. And that’s what is killing them now. BP and Shell have both written off more than $20 billion each in the last few weeks after writing down the value of reserves they now realise will not be extracted. They’ve seen the future, and it’s not petrol cars.

Big Oil in the US would do the same, were it not for the fact that they can kid themselves that somehow President Donald Trump or the Republicans will throw them a life line.

But they should look carefully at what the big utilities in the US and the coal companies are doing. The big utilities are making dramatic switches to renewables and storage, and by-passing gas along the way. The coal companies, one by one, are simply going bankrupt, or closing down.

The European energy giants, where government policy is a lot clearer, have made their own judgement and have been scrambling to restructure – mostly by splitting their business into the new and the old, the good and the bad, the future and the past, the clean and the dirty.

That way they can continue to tap profits from legacy assets up to the point where it is no longer possible, for social, political, environmental or economic reasons. Or a combination of all four.

“Nope, not us,” they will say of their old and dirty portfolio,” look at us now! – it’s all about distributed, digital and democratised energy – renewables and storage, and electric vehicles. Long live the customer!

In short, it’s the end of the ICE Age (internal combustion engine). That’s two trillion-dollar industries that Elon Musk’s upstart has overturned, with a third – electricity – coming next. But it will probably take an electric ute – from Tesla, Rivian or even GM, before the penny drops for some.

Giles Parkinson is founder and editor of The Driven, and also edits and founded the Renew Economy and One Step Off The Grid web sites. He has been a journalist for nearly 40 years, is a former business and deputy editor of the Australian Financial Review, and owns a Tesla Model 3.