New research has shown that plug-in hybrid electric vehicles (PHEVs) emit just 19 per cent less CO2 per kilometre on average than petrol and diesel cars in Europe, significantly undermining the claims of carmakers.

According to a new report published by Transport & Environment (T&E), a leading European clean transport and energy advocacy group, PHEVs were shown to emit roughly the same level of emissions as conventional hybrids and combustion vehicles.

This flies in the face of claims that PHEVs boast emissions as much as 75 per cent lower than conventional cars, as well as efforts by the automotive industry to weaken zero emission regulations by prolonging the sale of PHEVs beyond 2035 and versing the correction of official PHEV emissions.

The new report, Smoke screen: the growing PHEV emissions scandal, presents findings from an in-depth analysis of market and emission data for PHEVs across Europe.

The report focuses on both PHEVs as well as extended-range electric vehicles (EREVs), a specific PHEV variant that is becoming increasingly popular in China which uses a combustion engine to generate power for the battery.

“Plug-in hybrids are one of the biggest cons in automotive history,” said Lucien Mathieu, cars director at T&E.

“They emit almost as much as petrol cars. Even in electric mode they pollute eight times as much as official tests claim. Technology neutrality cannot mean ignoring the reality that, even after a decade, PHEVs have never delivered.”

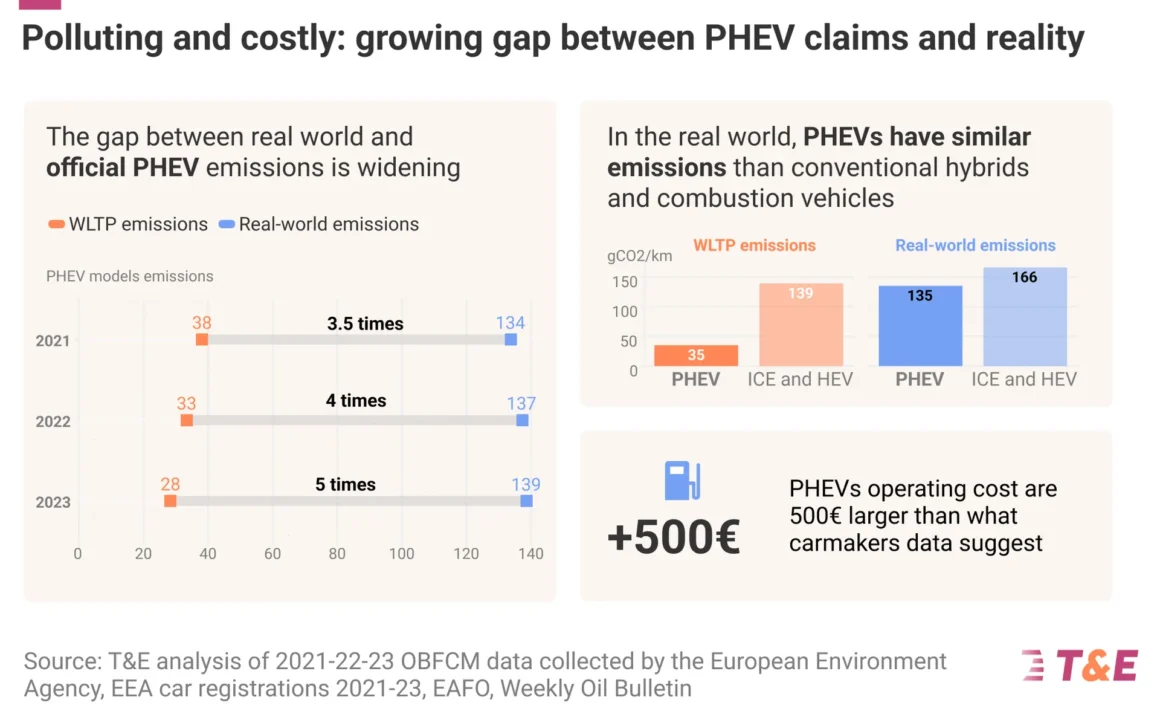

Some of the findings published in the report have already been highlighted by T&E, including the fact that the real-world emissions of European PHEVs are 135 grams of CO2 per kilometre (gCO₂/km) on average – five times higher than official tests suggest.

For comparison, petrol and diesel cars emit 166gCO₂/km.

The findings, which were first published in September, were based on an analysis of official European Union data sourced from fuel monitors on 127,000 PHEVs registered in 2023 across the EU. The data showed that between 2021 and 2023, the gap between official emissions and real-world emissions had expanded from 3.5 times to 5 times.

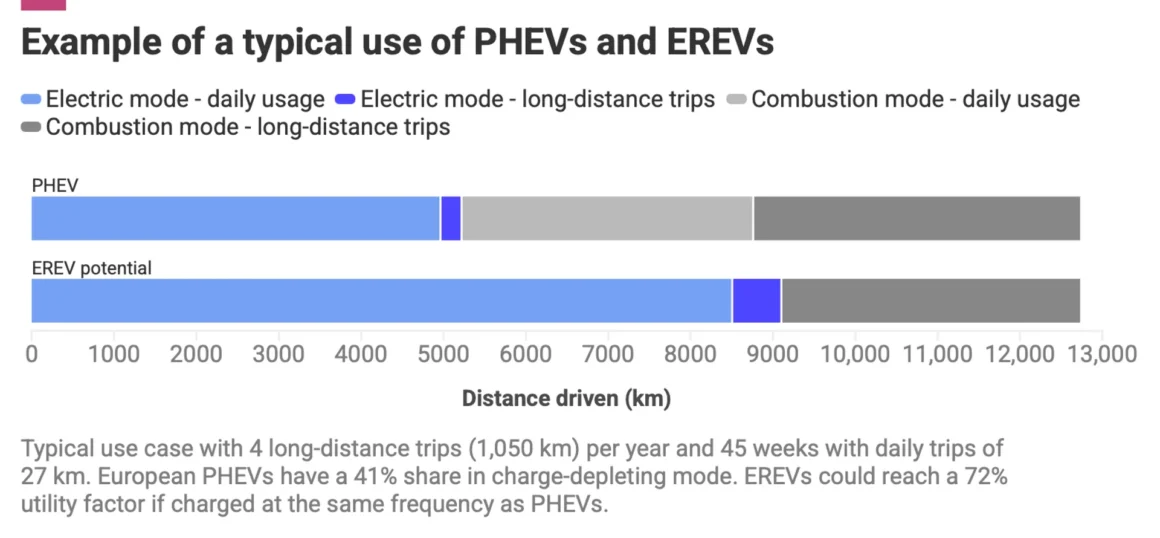

This gap is mostly attributed to flawed assumptions on the utility factor (UF) of PHEVs under the WLTP test methodology, which refers to the assumed distance drivers travel on electric-only mode.

Specifically, the UF used over the last few years has assumed that a PHEV with a 60-kilometre range will drive over 80 per cent of that distance using only its battery, whereas real-world data showed that number to be only 27 per cent.

New UF thresholds are set to be introduced which adjust that figure down to 54 per cent in 2025/26, and 34 per cent in 2027/28.

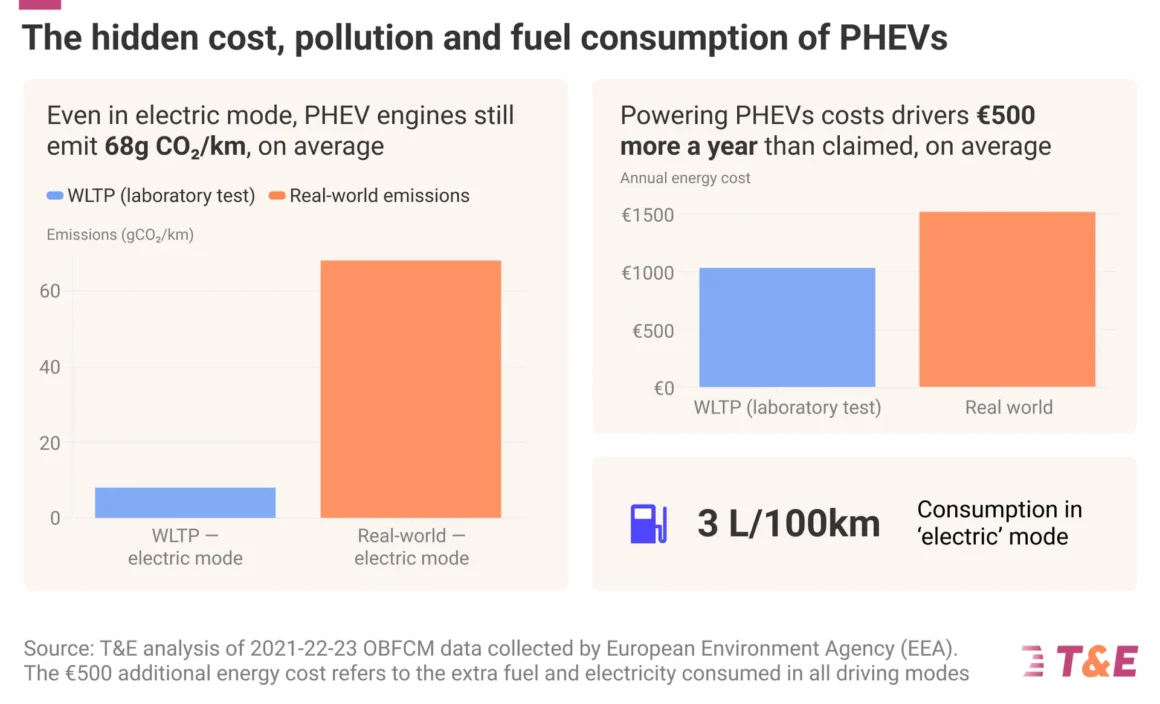

T&E’s analysis also showed that, even when driven in full electric mode, PHEVs still emit 68gCO₂/km, because the combustion engine still has to assist the electric motor.

“In practice, the combustion engine frequently assists the electric motor in CD mode, especially during acceleration, at higher speeds or uphill driving,” T&E concluded.

“On average, the ICE supplies power during almost one third of the distance driven in CD mode. This is largely due to insufficient e-motor power, as most PHEVs are not designed to operate fully electrically under typical real-world conditions.”

The real-world financial cost of this for drivers means an extra €250 in petrol costs every year, money that drivers did not expect to be paying considering they thought they were driving in electric-only mode. When taking into account charging costs, total energy costs for PHEV drivers grow to €500 more than expected, or around 50 per cent higher than official figures suggest.

These findings obviously undermine the claims of carmakers, who want PHEVs to be considered carbon neutral, but they also shine a light on the efforts of carmakers to cancel the planned correction to the assumed utility factor.

“If the utility factor corrections are not safeguarded, carmakers could rely heavily on overstated PHEV performance to meet their CO₂ targets, slowing the pace at which they increase BEV sales,” claimed T&E.

“As a result, fewer electric vehicles enter the market.

“Assuming a constant PHEV share, carmakers would need an average BEV share of 53% if both the 2025 and 2027 corrections of the utility factor are cancelled, instead of 58% under the planned utility factor updates. If PHEV production ramps up until 2030, with the market share of PHEVs doubling compared to 2025, the required BEV share could fall to just 45%, representing a shortfall of 13 percentage points (%p) in electric vehicles entering the market.”

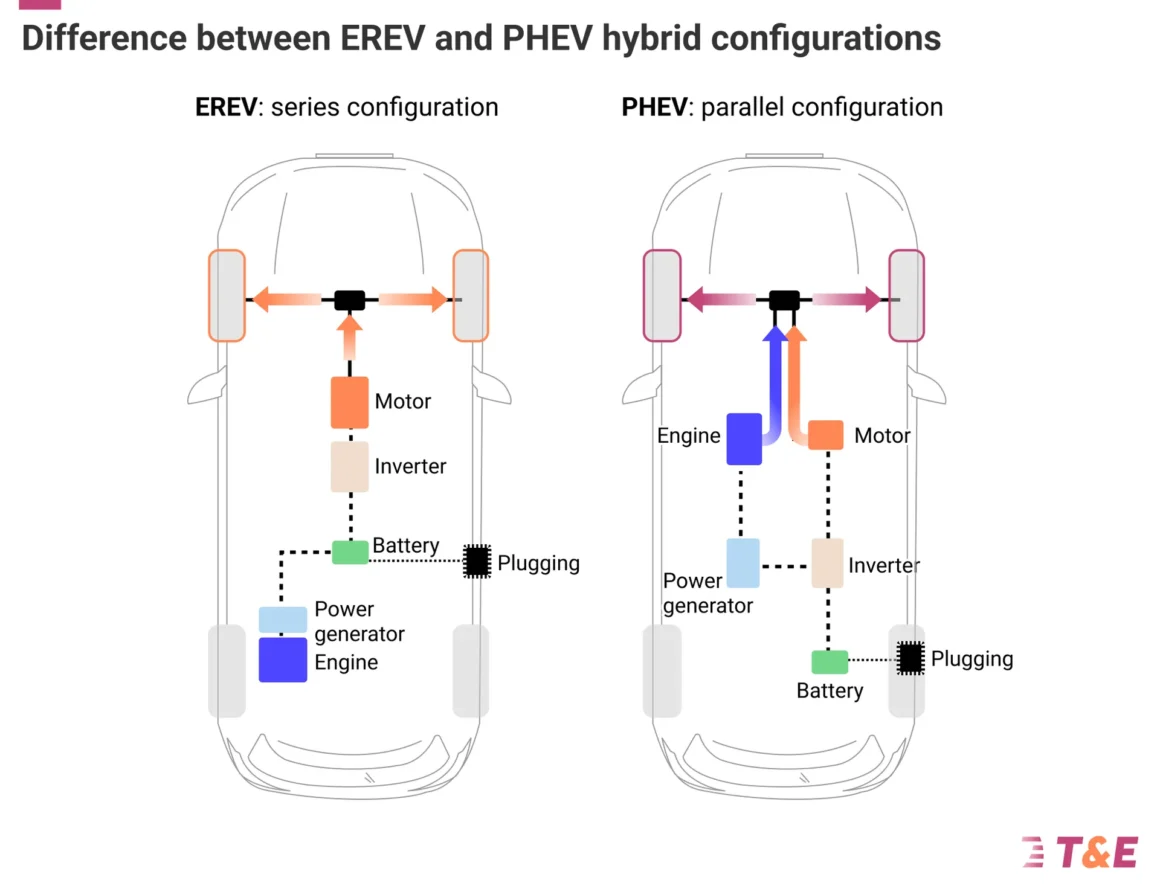

Extended-range electric vehicles (EREVs), like PHEVs, also rely on a combustion engine for their extended range, though they use a series configuration, which means that the combustion engine only ever recharges the battery and never provides power to the wheels directly.

According to T&E, EREVs usually have larger batteries than PHEVs and can therefore provide a longer electric-only range. This means that the combustion engine used for generating electricity is smaller than that found in a PHEV, since it does not need to provide power to the wheels.

However, even though EREVs can drive up to 900 kilometres, they are nevertheless still consuming 6.7 litres of fuel per 100 kilometres when in combustion mode – similar to some European petrol SUVs.

T&E claim that the real-world benefits of EREVs in Europe are uncertain, and offer only limited strategic or industrial benefits, considering that there is little domestic industry interest in EREVs and current supply chains are dominated by China.

Joshua S. Hill is a Melbourne-based journalist who has been writing about climate change, clean technology, and electric vehicles for over 15 years. He has been reporting on electric vehicles and clean technologies for Renew Economy and The Driven since 2012. His preferred mode of transport is his feet.