So you’ve bought an EV. Great! Job done?

Pardon the vernacular, but in Australia it’s a case of yeah, but nah, but…

Why it matters

Most EV owners are probably aware that their car creates more carbon emissions during the manufacturing phase of its lifecycle than comparable fossil burners.

But the gap is shrinking, and this initial emissions disadvantage is more than reversed during the use phase. The further a car is driven, the better for the planet that it is a battery EV rather than an ICE car – or a hybrid.

The point at which EVs become lower lifetime carbon polluters than their closest ICE equivalents depends on a number of variables and assumptions.

The most important variable is the energy source used to charge an EV. A 2023 report from the Electric Vehicle Council found that changing from an ICE to a BEV drivetrain would roughly halve the life cycle emissions of an average car driven on Australian roads.

But that reduction in emissions would halve again if the average car was recharged solely from solar PV, rather than from the average fuel mix in the National Electricity Market.

Another report, by Volvo in 2021, goes much further. In a head to head comparison of the fossil burning versus battery electric versions of its XC40 model, it found that charging only from wind power rather than from the global energy mix (which was, like Australia’s NEM, still heavily dependent on fossil fuel generation) resulted in a five times greater saving of lifecycle emissions compared to just switching from an ICE to a battery electric drivetrain.

There have been other reputable international studies in recent years which have produced findings which lie between those two by the EVC and Volvo.

Without getting into the details, I find it useful to summarise the whole field of lifecycle cycle emissions as implying that how we charge is probably just as important as (a) switching from a fossil burner to an electric car, and (b) choosing the most energy efficient EV we can get that meets our needs.

In Australia, cleaning up our charging act is not straightforward. About 60 per cent of all the energy traded in the NEM is still generated from fossil fuels: more in Victoria and Queensland; much less in South Australia and Tasmania.

To date, roughly 80 per cent of EV charging has been done at home, with the remaining 20 per cent split between destination chargers (7 to 22kW AC) and public fast chargers (50-350kW DC).

We have been relatively fortunate to date in that about one in three dwellings, and about 60 per cent of EV owners, have rooftop solar systems.

However, there is not a strong correlation between when the sun is shining and when many drivers need or are able to charge.

And much of the future mainstream uptake of EVs will need to be from EV owners and drivers who don’t have rooftop solar, especially apartment owners and renters. (For the sake of brevity and simplicity I’m putting aside the issue of workplace charging, but similar principles apply.)

So the energy source of public chargers matters. This is not a case of purchasing “green” versus “black” electrons when you plug in and tap, scan or autocharge. It’s a matter of whether the energy going into your car has been purchased by retailers on behalf of site owners or charge point operators (CPOs) from renewable energy or fossil fuel generators.

Claims and evidence

Given the still parlous state of public fast charging infrastructure in Australia, it’s not as if we are spoilt for choice in most parts of the country.

But as public destination and fast charging infrastructure improves, drivers may increasingly choose public AC destination and DC fast chargers which are guaranteed to be powered by renewable energy, and which are transparent about it when they aren’t.

Also, “powered by renewable energy“ may mean any of at least four distinct things:

- Some of the energy to charge cars is generated onsite, such as the famous Biofil system, which generates electricity from waste cooking oil, at the Caiguna Roadhouse, on the Nullarbor Plain. (This is relatively rare; drivers are lucky to get a roof over their car and the charger, let alone be under a solar roof big enough to charge multiple EVs.)

- The energy used to run the charging station itself comes from renewables, either onsite or via the site owner’s electricity supply contract. Sometimes referred to as ancillary loads, they comprise cooling systems, lighting, billing systems, communications, and grid interface hardware. Together, they typically make up five to ten per cent of the total electricity load of the site.

- The energy supplied through the grid to EVs while charging is from renewable generators. As explained above, this is physically impossible, but an equivalent amount may have been purchased via the NEM spot market, power purchase agreements, or the ASX energy futures market.

- The site owner or charging network operator has offset the emissions created by EV driving by purchasing and voluntarily surrendering large generation certificates (LGCs) which contribute to the creation of additional renewable energy capacity in the NEM.

It’s also worth noting that there are numerous parties involved in the provision of EV charging stations. The power generation fuel mix may be the responsibility of the site owner or the charge point operator (CPO). This can make it extremely difficult to figure out what the reality currently is at any given charging site.

So, if we want to maximise our emissions impact, what can we say about where and when to charge once we leave home?

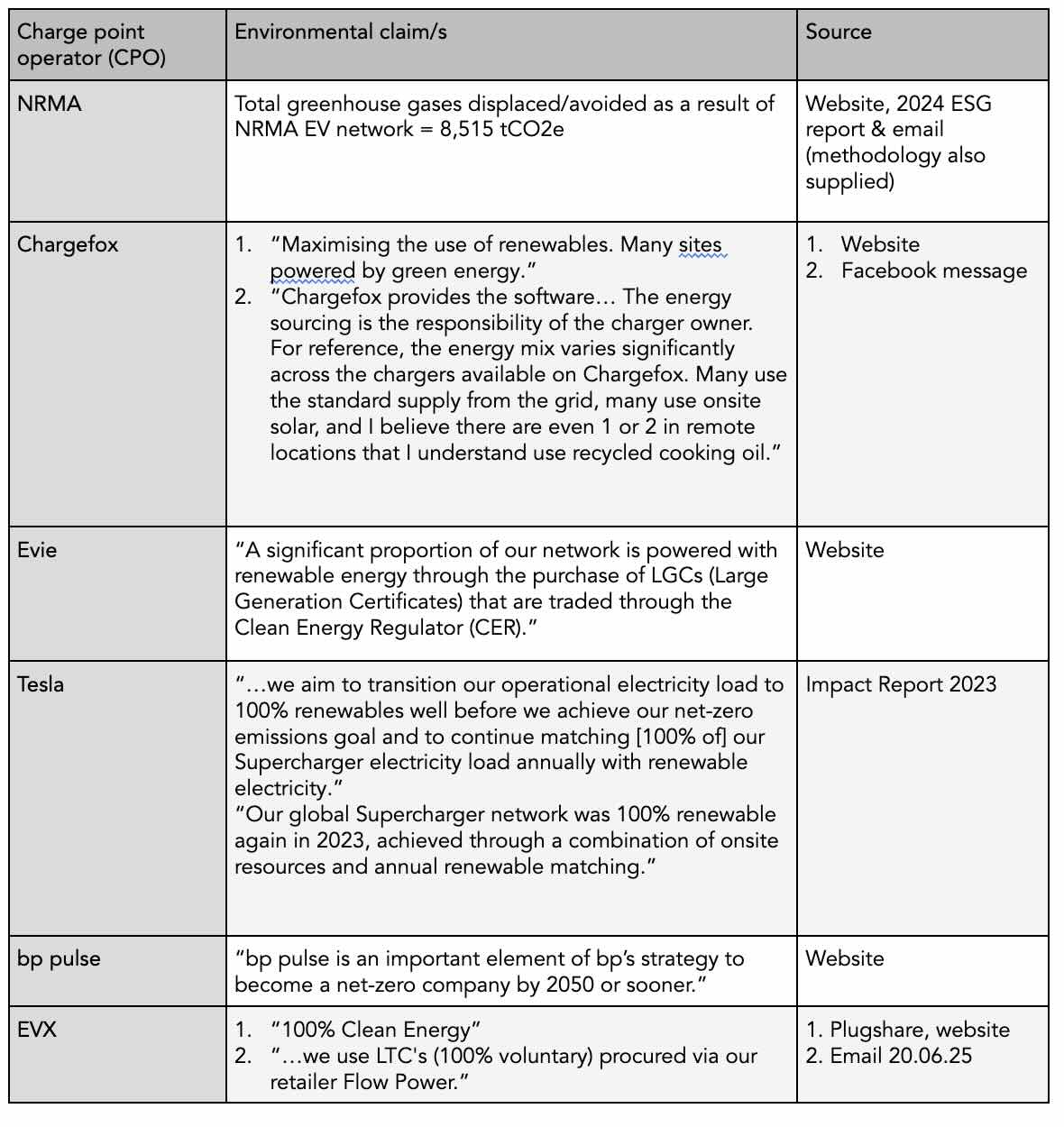

The table below is a summary of the public claims made by the main CPOs in Australia, as available on their websites or in related public documents; or alternately, in recent emails to me. If a CPO is missing—Exploren, Ampol, Everty, Origin 360, Jolt, etc.—it’s because it looks like they do not make any environmental claims publicly.

Tesla’s statements are indicative of the problematic nature of reporting on environmental claims. Deep in the bowels of its 2023 Impact Report it notes that: “For sites that include Superchargers, Tesla did not include electricity procured for customer use through the Supercharger stations as those emissions are included in Scope 3, Category 11 Use of Sold Products.”

In other words, Tesla is not claiming that the energy to charge your EV is purchased from renewable energy generators. It appears it is only the energy used to run the Supercharger sites themselves (category 2 above) that is 100 per cent renewable.

Dreamin’ on

Given the parlous state of EV charging across Australia, questioning the CPOs’ environmental claims at this point might be seen as a case of letting the perfect be the enemy of the good.

But for now, ignorance and confusion reign. As the public charging infrastructure evolves, at the bare minimum we need more transparency around where CPOs or site owners buy their energy from.

They should already know how to do this. Most public charging stations have been substantially funded by state and federal governments—especially via ARENA, whose grant criteria require applicants to demonstrate a “Commitment to source renewable energy and/or green certificates to cover 100% electricity use for BEVs.”

In practice, it looks like most grant recipients have used large generation certificates (LGCs), which are administered by the Clean Energy Regulator, to cover customers’ charging loads.

That is, they buy enough LGCs from complying wind and solar farms to cover (or “net off”) the remaining carbon emissions from the NEM grid supply (which varies by time and location). This money goes to the owners of new renewable power plants, stimulation the expansion of this sector and speeding the overdue demise of fossil powered plants.

Once the grant funding has run out, though (usually after two to three years), there is no external scrutiny. It looks like some CPOs and site owners are continuing to buy LGCs, but others have dropped their earlier mandatory commitment to 100 per cent charging from renewables. It’s difficult to be more specific when terms like “some”, “many” and “a significant proportion” are used.

For the time being, in spite of criticisms around the quality of offsets it purchases, probably the best option is for CPOs to join Climate Active. This is a federal government scheme which awards its certification to “organisations that have credibly reached a state of carbon neutrality against the requirements of the Climate Active Carbon Neutral Standard.” Operators could then promote or brand their complying charging stations accordingly.

Alternately, governments and industry could work together to develop and implement a “green star” rating system such as those for electrical appliances and new buildings that already exist in Australia. Ideally it would cover all four of the “powered by renewables” scenarios discussed above.

We can only dream of the day when EV charging stations have largely replaced petrol stations, and green star ratings are advertised alongside charging tariffs on every charging station. Oh, and a (solar) roof would be nice, too.

Mark Byrne is an independent energy and EV analyst. He co-created the Green Electricity Guide (with Greenpeace) and the 2023 Green Electric Car Guide (with the Total Environment Centre). Thanks to to Tristan Edis and Andrew Fowler for their input.