‘Mini’ and ‘micro’ EVs, small affordable cars weighing 700 kg to 1200 kg with sustainable carbon footprints are not currently marketed in Australia.

This is due in large part to the perverse consequences of the current flawed Australasian New Car Assessment Program (ANCAP) crash ratings. Even more egregious is the fact that there are no safety star ratings for vehicle CO2 and toxic exhaust pollution. There are many more deaths from these causes, and large vehicles are the worst culprits.

ANCAP crash ratings ignore the ‘elephants in the room’

Large SUVs and 4WD are generally considered ‘safer’ for their occupants, in the event of collisions with smaller vehicles.

However, research using US Fatality Analysis Reporting System data in 2021 shows that when cars collide head on with large 4wd utes and SUVs and cars, the odds of death for the car driver are 7.6 higher than the SUV driver, regardless of crash star rating.

For pedestrians and cyclists, risk of fatalities from vehicle strikes is 2.3 higher for large 4wd utes and 1.7 times higher for other SUVs than for sedans and hatches. Children are 8 times more likely to die when struck by a SUV compared to children struck by a passenger car.

Existing ANCAP scores encourage people to buy larger vehicles with 5 star ANCAP crash ratings rather than smaller, less polluting models that may have 3 to 4 star ratings.

ANCAP rates safety of vehicle occupants in collisions with a 1400 kg trolley the size of a family car, thus tending to award 5 star crash scores to larger vehicles despite their lethality to pedestrians and drivers of smaller vehicles.

For example, the Ford Ranger large 4wd are actually given a better score under the ‘vulnerable road users’ criterion than the small VW Polo hatch. ANCAP crash ratings clearly need to be reworked:

- Existing ANCAP ‘vulnerable users’ scores are contradicted by the peer reviewed research.

- Lethality to occupants of smaller vehicles is not included in the ANCAP criteria.

- ANCAP ratings exclude likelihood of collisions due to a vehicle’s blind spots and obstruction of other drivers’ view, all of which are worse for large vehicles.

If the above factors were included in the ANCAP ratings, true crash lethality would be reflected and it is likely no large 4wd SUV would achieve a 5 star rating.

The Federal government is further complicit in encouraging purchase of large SUV’s by enabling tax write-offs for any ‘business use’ even if they are only transporting the driver, and classifying 2-3 tonne passenger utes and wagons as ‘commercial’, making them exempt from luxury car taxes and giving them a 5% -20% price discount over much less polluting EVs.

CO2 and toxic air pollution are many times more lethal than crashes but are not included in vehicle safety ratings

Toxic vehicle pollutants cause up to 11,100 deaths per year in Australia, which is 9 times more than the 1200 vehicle crash deaths and almost as many as cigarette smoking.

Nitrogen dioxide from diesels is responsible for more than 80% of these deaths and micro particulates from tyres and smoky exhausts more than 10%. Pollution increases with vehicle weight, power and age. A large diesel SUV will emit several times more pollution than a small petrol hatchback.

Carbon dioxide pollution, though odourless and invisible is having an even greater impact than toxic pollution. Thirty percent of each kg of CO2 emitted will still be in the atmosphere in 1,000 years, adding to global warming, which has already reached 1.5 degrees C above the 1950-1980 norm.

A 2023 study estimated that CO2 emitted by the Australian vehicle fleet this year will cause 30,000 to 100,000 climate related deaths in the 76 years to 2100. That is 3 to 10 times more deaths than toxic exhaust pollution and crashes combined.

If carbon emissions continue to increase at the current rate resulting in global temperature rise of 4 degrees by 2100, about 1475 tons of CO2e is forecast to cause one death from climate related causes including temperature stress, disease, famine drought and floods.

Some high emitters emit this much carbon in their lifetime and will be responsible for the death of one person in their grandchildren ’s generation.

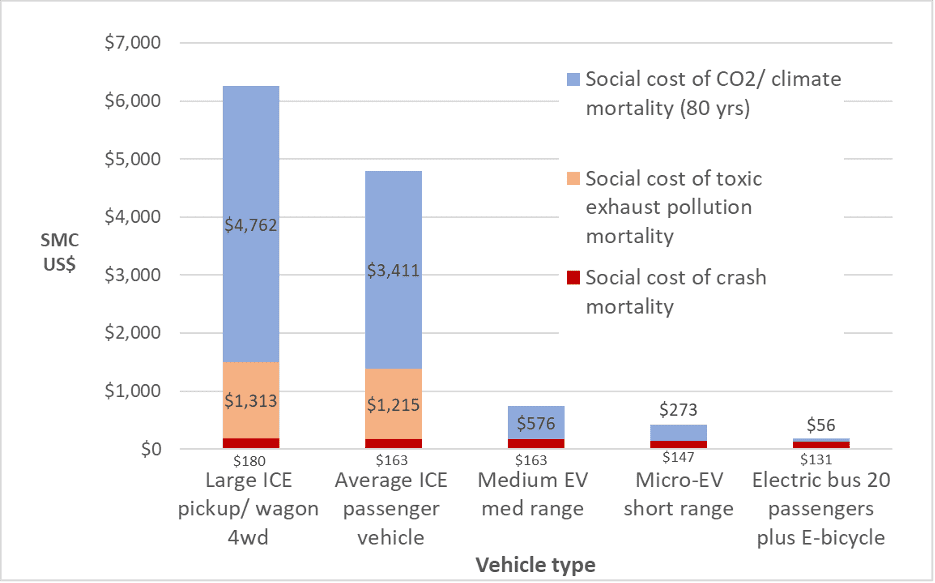

Social cost of carbon mortality is calculated by monetizing carbon mortalities using a global value of a statistical life year (US $48,000). It can potentially be used to estimate taxes on vehicles and fuels. Figure 1 below illustrates the relative social cost of vehicles due to climate mortality, exhaust pollution and crashes.

What is a sustainable vehicle?

While a sustainable vehicle needs to be safe for its occupants, it is much more important that it has low CO2 emissions and no toxic exhaust emissions. The only practicable available options that fit both of these criteria are battery electric vehicles (BEVs).

Figure 2 below shows the carbon emissions of various vehicles over an assumed life of 15 years and 225,000 km. The horizontal dotted line is the sustainable personal carbon footprint (SPCF) of 2 tCOe per year, which must be achieved by everyone if carbon emissions and therefore temperatures are to stop rising.

Transport by car can comprise up to 25% of a SPCF. It is evident that no fossil fuelled vehicle is compatible with a SPCF.

A key point to note is that for fueled vehicles the main sustainabilty issue is the operational emissions while for EVs it is the embodied emissions. When an EV is running on 90% renewable energy (as is assumed in Figure 2), 80% of its carbon emissions are embodied in the manufacture of the vehicle and battery.

In short, public transport and E-bikes are the most sustainable options for one person. A micro-EV may also be accommodated in a SPCF for one person.

‘Mini’ EVs up to 1.2 t mass and 40 kWh battery capacity (actually adequate for families) can make the grade only when co-owned/ shared by at least two people, medium EVs by at least 3 people and large EVs by at least 4 people.

Total vehicle related deaths would be reduced by more than 90% due to reduced air pollution and per social cost savings of $5000 per capita could be realized (Figure 1) if everyone used these modes.

However, passenger vehicles are getting bigger and heavier. Mid-sized family cars are now called minis. This is probably another ploy by the motor industry to increase their profits by encouraging people to buy bigger more expensive vehicles.

Compared to the BYD Dolphin Mini (Figure 4a), the 1964 EH Holden (Figure 3a), which provided adequate transport for our family of 5 was the same weight and width, 17 cm longer, 5 cm lower and had smaller (13 inch) wheels. The EH has identical acceleration, but its energy costs are 3 times higher than the EV and air pollution many times higher.

The Dolphin Mini has a range of about 310 km with highway driving at 90 kph, a top speed of 130 kph and is adequate sustainable transport for a family of 4.

A new electric version of the robust, 700 kg Manx buggy I owned in 1973 (Figure 3b) can be bought and licensed in the US, but is not sold here.

They would be a cheaper and less lethal option in terms of CO2 and toxic air pollution for those who drive large 4wds for commuting and recreation. It would be a shame if the lack of a 5 star ANCAP star crash rating means they will not be sold here.

The Misubishi EKX pictured in Figure 4b is a Japanese micro (‘kei’) EV, with a range of about 180 km. It provides adequate sustainable urban transport for 2-3 people.

Both the Dolphin Mini and the EKX have right hand drive versions but neither can be bought in Australia, though they are among the most popular cars in Asia and there is a huge need for affordable sub $25,000 EVs here.

Today’s ‘Mini’ EVs are actually safe family cars. They have four or more airbags, ABS braking and stability control but most would only get a 3 star crash rating.

The Mitsubishi Australia CEO is considering marketing the EKX in Australia but is impeded by the perception that new vehicles must have costly 5 star occupant protection and collision avoidance systems.

Five star crash ratings should never be complusory and are only beneficial for those who do a lot of high speed driving or who are prone to fatigue. It is worth noting that a US study (Figure A1) showed there has been little if any decrease in road crash fatality rates since 2010, when the 5 star rating was equivalent to 3 stars today.

Recommendations and conclusion

Governments should:

- Implement vehicle CO2 and toxic air pollution star ratings for vehicles, with priority over crash star ratings.

- Educate the public about vehicle CO2 and toxic air pollution.

- Amend the NCAP crash rating system as described in Section 2.

- Increase vehicle licensing or third party insurance rates for large polluting vehicles and decrease them for small EVs, to reflect social cost of CO2 and toxic air pollution.

- Apply a carbon mortality taxes to fossil fuels.

There were 48,000 heat deaths in the EU in 2023, more than double the 20,400 road crash deaths. But governments spend millions trying to reduce road crash deaths while turning a blind eye to worsening climate mortality.

Appendix