The global road transport sector can still reach net-zero emissions by 2050 through electrification, but urgent action is vital, and the last internal combustion vehicle (ICE) must be sold by 2038.

A new analysis from research company BloombergNEF (BNEF) the window to stay on track for net-zero road transport emissions by 2050 is still open. “But only just barely,” says Aleksandra O’Donovan, head of electric vehicles at BNEF.

“A big push is needed from governments, automakers, part suppliers and charging infrastructure providers in the years ahead.”

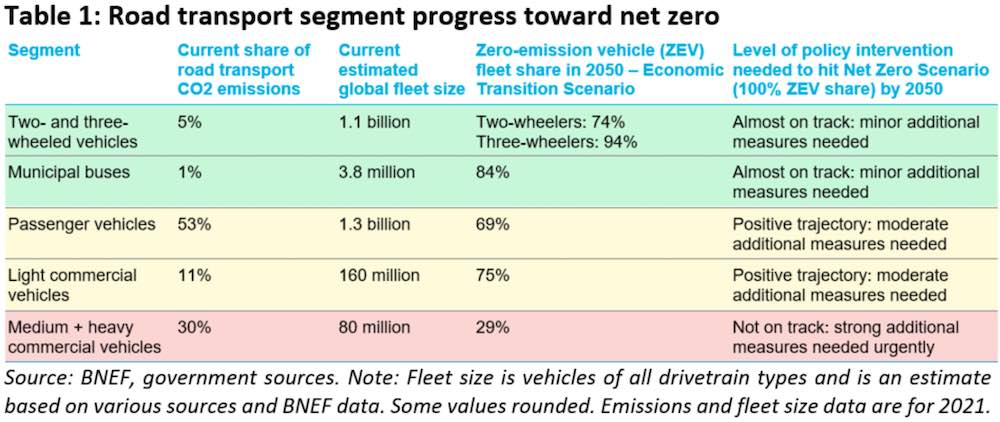

Currently, certain segments such as buses and two- and three-wheelers are close to being on track for net-zero, but more action is needed in other segments to get on track for net-zero by 2050 – especially in medium and heavy commercial vehicles.

A table provided by BNEF shows that passenger vehicles and light commercial vehicles require a moderate amount of additional measures put in place to acheive net-zero goals.

However, it says that “strong additional measures” are urgently needed if medium and heavy duty vehicles are to meet zet-zero targets.

According to BNEF, passenger EV sales are set to accelerate rapidly over the next few years, jumping from 6.6 million sold in 2021 to 21 million sold in 2025.

Meanwhile, the fleet of EVs driving on our roads will grow from 16 million at the end of 2021 to hit 77 million by 2025 and 229 million by 2030.

This growth in EV uptake is already displacing 1.5 million barrels of oil demand per day – though most of this is from electric two- and three-wheelers in Asia. However, rising passenger EV sales will push this to 2.5 million barrels per day by 2025.

Oil demand by transport to peak in 2027

Overall, according to BNEF, oil demand from road transport will peak by 2027, as electrification spreads to all other areas of road transport beyond only passenger vehicles.

Similarly, sales of internal combustion engine (ICE) vehicles already peaked in 2017, according to BNEF, who expects the global fleet of ICE passenger vehicles to start declining starting in 2024.

However, to get on track for a net-zero global fleet by 2050, zero-emission vehicles need to account for 61% of global new passenger vehicles sales by 2030, 93% by 2035, with the last ICE vehicle of any segment needing to be sold by 2038 at the latest.

“Electric vehicles are a powerful tool in reducing global CO2 emissions from the transport sector,” said Colin McKerracher, head of the advanced transport team at BNEF and lead author of the report.

“There are very positive signs that the market is moving in the right direction, but more action is needed – especially when it comes to heavy trucks. Action also needs to focus on emerging markets, which need financial support to help enable and accelerate the transition to electric mobility of all types.”

Urgent action needed to reach net-zero transport scenarios

BNEF’s EVO outlines two scenarios for the uptake of electric transport through to 2050, examining for both the impacts on demand for batteries, materials, oil, electricity, infrastructure, and emissions.

The two scenarios are the Economic Transition Scenario (ETS), which assumes no new policies and regulations are enacted and the transition is driven by techno-economic trends and market forces, and the Net Zero Scenario (NZS), which is driven primarily by economics.

Urgent action is needed across both scenarios, however. BNEF points to the need for developed countries and multilateral institutions to include EV investments, incentives, and charging infrastructure deployments in their international climate finance plans, making capital available to emerging economies that have credible plans to develop a zero-emission vehicle sector.

Between the two scenarios in BNEFs report, the passenger EV fleet is expected to hit 469 million in 2035 in the Economic Transition Scenario, but needs to jump to 612 million by the same date in the Net Zero Scenario – a gap which must be met by emerging economies who are supported by wealthier countries so as to avoid a global slowdown of adoption.

Battery electric versus hydrogen transport

The BNEF EVO also explores whether batteries or hydrogen fuel cells will be the more likely solution for electrifying heavy-duty long-haul freight. It finds that – as megawatt-scale charging stations and the emergence of higher energy density batteries become more commonplace by the end of the decade – battery electric long-haul operations will become more viable.

Hydrogen fuel cell vehicles may be able to help fill gaps here and there, especially in areas where electrification cannot reach – such as heavy vehicles, in some regions, or in duty cycles where batteries struggle.

Finally, the report notes that reducing car dependence through the prioritisation of public transport, walking, cycling, and other measures should be pursued wherever possible.

Specifically, even a 10% reduction in kilometres travelled by car by 2050 alone would lead to 200 million fewer cars on the road, reducing cumulative CO2 emissions by 2.25 gigatonnes. Such a decrease would also greatly alleviate strain on the battery supply chain.

Joshua S. Hill is a Melbourne-based journalist who has been writing about climate change, clean technology, and electric vehicles for over 15 years. He has been reporting on electric vehicles and clean technologies for Renew Economy and The Driven since 2012. His preferred mode of transport is his feet.