Volvo and Volkswagen are the only incumbent carmakers on track to make a successful shift to electric vehicles in time to meet European emissions targets, with many big names – including Ford, BMW, Daimler and Stellantis – way behind, according to a new report.

Toyota, Japan’s and the world’s biggest carmaker in terms of cars produced and sold, is the pre-eminet laggard among the 10 biggest incumbent carmakers producing cars in Europe, the study found, having bet too long on hybrids (just as Australia is now doing).

The report, by European pro-EV campaign group Transport & Environment, gives scores out 100 to the 10 biggest carmakers with production plants in Europe for their readiness for electrification.

Europe has some of the most aggressive pro-EV laws in the world, where EV sales are already 10 per cent of total sales. So carmakers that succeed in making the shift in the EU will likely come to dominate the EV market elsewhere.

Volvo and VW were each given 70 out 100, and were the only carmakers considered to have credible processes in place to reach their goals. Toyota, on the other hand, was given just 35 out of 100 and labelled a “serious laggard”.

In the middle of the pack sat American carmaker Ford, with 46 out 100, and Germany’s Daimler (manufacturer of Mercedes) and BMW, on 46 and 44 respectively.

South Korea’s Hyundai, which includes Kia, received 52 out of 100, and the Renault-Nissan-Mitsubishi Alliance, manufacturer of the popular Nissan Leaf, was in third spot on 57.

Stellantis, the world’s newest car giant that was created this year through the merger of Fiat Chrysler Automobiles and the French PSA Group (maker of Peugeot), was given a lackluster 46.

Tesla was not included in the study because it is already 100 per cent electric. Transport & Environment said they would have topped the list had they been included.

The study examined each carmakers readiness for the EV transition by looking at things such as EV architecture, technology mix, action in battery supply chains and infrastructure.

The overall picture was not encouraging. While many carmakers have been talking up their plans, the report found very few had credible plans to get there. Of the two leaders, Volvo has the most ambitious plan – it wants to be 100 per cent electric by 2030.

VW’s ambitions are more modest. It’s aiming to be 60 per cent electric by that date. However, Transport & Environment found VW was ahead of Volvo in “industrial transition”.

It found players like Renault, Hyundai and Ford had fairly ambtious targets, but lacked “robust plans” to reach them. It found Germany’s prestige car makers, BMW and Daimler, were relying too heavily on hybrids.

Of Toyota, the report was scathing: “Toyota comes last and, having bet on hybrid solutions for too long, is now a serious laggard in the electrification revolution that is underway.”

Julia Poliscanova, senior director for vehicles and emobility at the NGO, said: “Carmakers are desperate to show off their green credentials, but the reality is most of them are miles away from where they need to be. Even those that are ambitious lack a suitable strategy to get there. Carmakers have failed to deliver on their promises before, who says this time will be different?”

That scathing assessment is relevant to another laggard, Australia, where the federal government’s so called “future fuels policy” (FFS) focuses almost entirely on hybrid cars, despite its near total dependence on imported fuels. Toyota is considered highly influential in Australian policy development because of its pre-eminent position in total car sales.

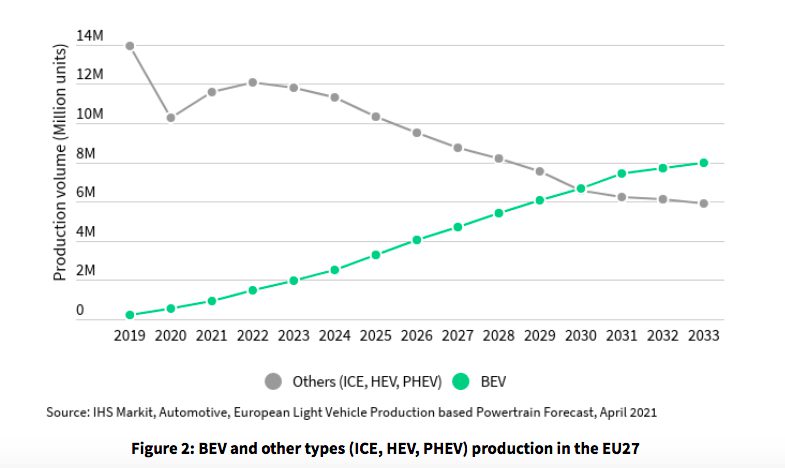

On the upside, the report said by 2030 battery EVs were on track to dominate car production in Europe, going from 530,000 vehicles in 2020 to 3.3 million in 2030. But it said the transition was simply not happening fast enough.

The report found on current trajectories, battery EV sales would be 10 percentage points below where they need to be by 2030 to meet overall emissions goals. It called on the EU to tighten its ambitions so that two thirds of cars sold in Europe in 2030 are battery EVs, reaching 100 per cent by 2035.

The UK, which is no longer part of the EU, will ban the sale of pure petrol and diesel cars by 2030, and hydrids by 2035.

The EU already has some of the strictest CO2 emissions standards for cars in the world, and rewards carmakers that increase EV production. However, the policies have been far from satisfactory, and emissions from transport have risen about 20 per cent since 1990, where in all other sectors (apart from refrigerants), they have fallen.

The European Commission, the executive arm of the EU, is in the process of drawing up a suite of policies that will radically ramp up its decarbonisation strategies to meet its new emissions reduction target of 55 per cent by 2030. It is expected to drop the new policies – numbering hundreds of pages – in August.

James Fernyhough is a reporter at RenewEconomy and The Driven. He has worked at The Australian Financial Review and the Financial Times, and is interested in all things related to climate change and the transition to a low-carbon economy.