Australia’s main scientific research body, the CSIRO, says Australia’s entire car fleet could be fully electric by 2050, with the share of EVs in new car sales reaching more than 70 per cent as early as 2030 and 100 per cent of new car sales by 2040.

The forecast is one of five scenarios canvassed by the CSIRO for electric vehicles, rooftop solar and battery storage to help inform the 20-year blueprint – known as the Integrated System Plan – being put together by the Australian Energy Market Operator.

The scenario for the switch to a fully electric fleet is significant because it is included in the “step change” scenario, the one newly introduced by AEMO to assess what is required of Australia’s grid to contribute to the Paris climate targets of limiting average global warming to well below 2°C, and as close to 1.5°C as possible.

Naturally, it assumes a zero emissions target by 2050, and the “step change” scenario points to a share of renewables of more than 90 per cent within two decades.

Even in AEMO’s central scenario, based on existing or announced policies, the share of renewables is well above 70 per cent because of the need to replace ageing coal generators with the cheapest option, which AEMO and CSIRO agree is wind, solar and storage.

The management of the grid in the next two decades also needs to factor in the electrification of transport. And CSIRO’s forecasts signal a huge increase in electricity demand as the entire car and light commercial fleet goes electric, and much of the heavy trucking fleet does too.

Australia currently trails the developed world in the adoption of EVs, even though the arrival of new models such as the Tesla Model 3 and the Hyundai Kona provided a boost, albeit from a small base, in 2019.

Australia, CSIRO notes, is also the only country in the developed world that does not have vehicle greenhouse gas emission or fuel economy standards, which means that vehicles sold in Australia are generally 20 per cent less efficient than the same model sold in the UK, adding significant fuel costs for consumers.

Even government studies have estimated that the cost of this inefficiency is about $600 a year, per vehicle. Bizarrely, the federal government has refused to introduce new standards because of the weight of a Murdoch-media campaign that claims such a move would amount to a carbon tax on wheels.

The CSIRO study does not lay out a prescriptive policy path to reach the “step change” scenario and a totally electric fleet, but it does assume that “price parity” between electric and petrol cars is reached by 2025 (as opposed to 2035 under the slow change scenario), and that other limitations, such as infrastructure (charging stations) are not a restraint.

“Low emission vehicles such as electric vehicles are expected to be adopted with or without emission standards, but new policies could accelerate their adoption,” the CSIRO notes. The federal government has so far expressed it does not intend to establish targets for EV uptake.

The CSIRO says that getting EVs to a high share of new car sales is one thing, but changing the whole fleet is another – that’s because it can take more than 20 years for a market share to translate into a fleet share because of the length of time that vehicles are used.

So the above graph assumes that “fleet scrapping rates” accelerate from the 2030s. This accelerated scrapping rate could be driven by a policy mechanism or it might occur naturally as a product of market incentives and sentiment.

“Several states have policies to achieve zero net emissions by 2050 and may consider measures to support that in the road transport sector,” it says.

“Market incentives might include a rapidly declining choice of places to refuel and maintain internal combustion vehicles as electric vehicles become dominant. Changes in sentiment might include a shift in views about the economic viability, perceived performance and social acceptability of maintaining internal combustion vehicles.”

It likens this to the broad scrapping of often still functioning non-flat screen televisions in the last two decades.

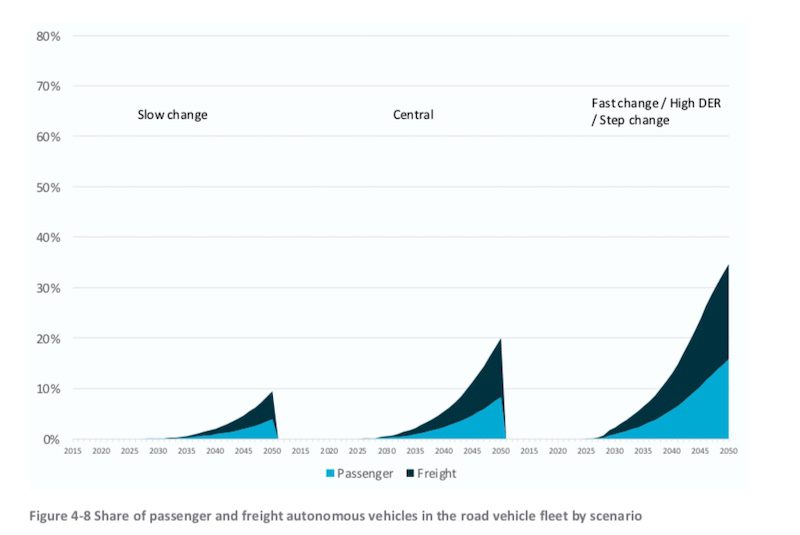

Another interesting data point included in the CSIRO report is the share of autonomous vehicles. This graph belows show up to 35 per cent in the faster scenarios, with more than half of them coming from freight vehicles, and slightly less than passenger vehicles.

The presence of autonomous vehicles, and the growth of ride sharing, may mean that there are less vehicles on the road than otherwise might have been expected.

Still, the electricity demand from the transition to a fully electric fleet will be significant. This next graph shows that the “step change” scenario is the outlier, but could add 140,000 GWh in demand on to the grid.

That’s an increase of more than 50 per cent from current demand, and will require some significant management to ensure charging times are callibrated in demand.

On the other hand, it could deliver a significant resource for the grid operator if vehicle and vehicle-to-grid technologies are fully exploited. And, as the CSIRO has also forecast, the amount of rooftop solar could also increase substantially.

It has lifted its ‘step change” forecasts for small scale rooftop solar to nearly 60GW, a 50 per cent lift from its previous scenarios.

Giles Parkinson is founder and editor of The Driven, and also edits and founded the Renew Economy and One Step Off The Grid web sites. He has been a journalist for nearly 40 years, is a former business and deputy editor of the Australian Financial Review, and owns a Tesla Model 3.