As the world waits for electric car pioneer Tesla to reveal the secrets of longer lasting, more efficient batteries at its upcoming Battery Day, it’s worth brushing up on why several of Tesla’s patents have caught a great deal of attention.

Tesla’s tabless battery patent, a “lithium doping” patent, and a single crystal cathode patent are three patents that will potentially play key roles in more efficient and longer lasting batteries.

Arguably the most important of these is the single crystal cathode patented for Tesla by Dalhousie academic and head of the Tesla battery research team, Jeff Dahn.

In a paper published by Dahn and his team in the Journal of The Electrochemical Society regarding the significance of the single crystal cathode, he says: “We conclude that cells of this type should be able to power an electric vehicle for over 1.6 million kilometres (1 million miles) and last at least two decades in grid energy storage.”

Enabling an electric car battery to last a million miles (or, 1.6 million kilometres) will mean that the battery pack lasts as long as the electric car it powers.

According to Tesla CEO and co-founder Elon Musk, the EV maker’s best selling Model 3 is designed to last one million miles, but current battery chemistry used by Tesla only lasts for up to 500,000 miles (800,000km) – or, 1,500 cycles.

“Model 3 drive unit & body is designed like a commercial truck for a million mile life. Current battery modules should last 300k to 500k miles (1500 cycles). Replacing modules (not pack) will only cost $5k to $7k,” wrote Musk on Twitter in 2019.

Model 3 drive unit & body is designed like a commercial truck for a million mile life. Current battery modules should last 300k to 500k miles (1500 cycles). Replacing modules (not pack) will only cost $5k to $7k.

— Elon Musk (@elonmusk) April 13, 2019

Why the single crystal cathode patent, titled “Method for synthesizing nickel-cobalt-aluminium electrode“, is so significant is explained in greater detail by Youtuber The Limiting Factor.

The main points are:

- A battery with a single crystal cathode will suffer less degradation

- With the right electrolyte solution and additives, such a battery could cycle 4,000 times

- The patent’s processes are not limited to the use of nickel-cobalt-aluminium chemistry

We summarise here:

Made of nickel, cobalt and aluminium (NCA), the genius of the single crystal cathode is in its simplicity.

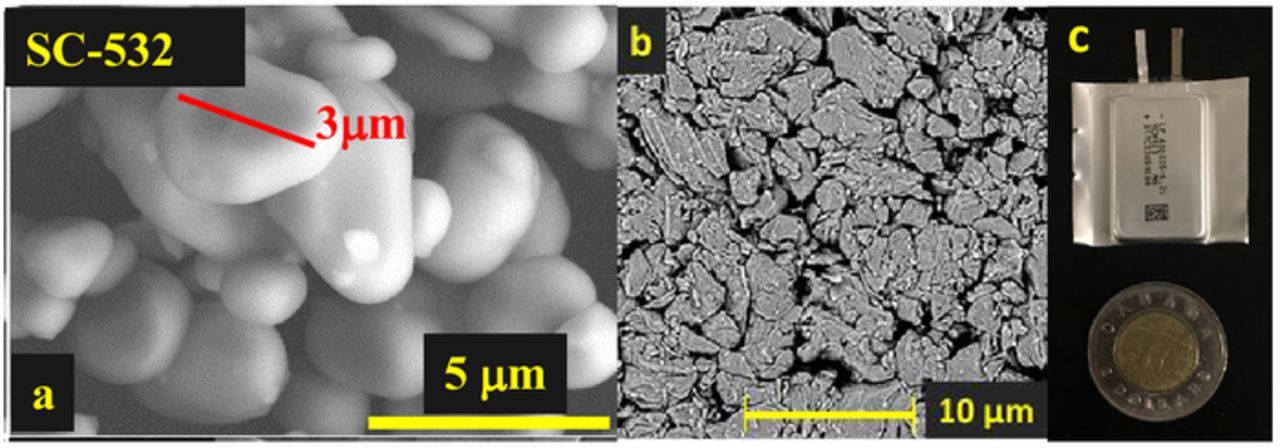

How simple? Instead of using a “polycrystalline” structure made of many crystals fused together, the single crystal cathode is made of larger single crystals that all face the same way, instead of in many different directions.

This is important because, as The Limiting Factor notes, “as a lithium-ion battery charges and discharges, lithium ions enter and exit the space between those rows of atoms which causes individual crystals to expand and contract.

“This creates stress at the crystal borders because the crystal structure is aligned in different directions and therefore expands and contracts in different directions. Over time, the polycrystalline structure tears itself apart of the seams, that crystal disintegrates and the battery fails.”

Larger single crystals don’t suffer this problem inherent in polycrystalline structures, because as the rows of atoms are facing the same direction in every part of the crystal, they don’t suffer the same amounts of stress.

“Even better, with the right coatings and additives they can last for thousands of cycles,” adds The Limiting Factor creator.

But there’s more. Although the title of the patent refers to nickel-cobalt-aluminium as the materials used in the patent, it’s important to note that it is the method, not the materials that are significant.

This is important: because the wording of the patent intentionally leaves room for use of a cobalt-free chemistry, which would potentially reduce the cost of making battery cells and also allow Tesla to move away from sourcing material from an industry that is known for child labour.

As The Limiting Factor creator notes, fellow inventors of the patent, Hongyang Li and Jing Li have also worked together on a cobalt-free chemistry.

The patent also discusses what is different about Tesla’s patent that enables it to be patented – namely, the way in which it says is can make the single crystal NCA material.

To make single NCA crystals, high temperatures must be reached. Unfortunately this can create excess reactions between the lithium and other materials, resulting in low purity material and therefore a less energy dense battery.

How Tesla achieves this is explained in-depth in the video (that you can view below), suffice to say here that Tesla’s battery research team have solved this problem in a two-step process.

Importantly, the patent also states in paragraph 14 that the process can be repeated with a range of other materials such as a aluminium, nickel, cobalt, manganese and magnesium.

“It is worth noting that these are the same metals that Hongyang Li, Jeff Dahn and Jing Li tested in the paper outlining a cobalt-free battery,” notes The Limiting Factor presenter.

The single crystal cathode patent does not in itself mean Tesla has worked out how to make a battery that lasts 1.6 million kilometres, or a million miles.

The patent does show that single crystal cathodes clearly degrade more slowly, as mentioned above, it will also need to use the right electrode and additives.

The Limiting Factor suggests that Tesla will use a titanium coating that could extend battery life even more than the single crystal cathode alone – and notes that Dahn and his team have been working on such a coating.

He also notes that Tesla may also have an alternative battery additive to lithium difluorophosphate, which he says is the most effective additive on the market for extending battery cycle life.

While lithium difluorophosphate would be a useful additive, it is patented by Mitsubishi Chemical Corp and would therefore be very expensive to use.

However, The Limiting Factor believes that Tesla could be filing a patent instead for sodium difluorophosphate.

In a paper that reviewed electrolyte design published in Cell by Jeff Dahn and research associate ER Logan in April, he notes that, “recent work has identified new Li salts and other additives that form favorable SEI layers for fast charging, such as difluorobis(oxalato) phosphate.”

“I expect Tesla has filed a patent for this and they’ll be making this in-house as well,” says The Limiting Factor.

Citations:

A Wide Range of Testing Results on an Excellent Lithium-Ion Cell Chemistry to be used as Benchmarks for New Battery Technologies

, , Publication Date: 6 September 2019

http://dx.doi.org/10.1149/2.0981913jes

Is Cobalt Needed in Ni-Rich Positive Electrode Materials for Lithium Ion Batteries?

, ,

Publication Date: 6 February 2019

https://doi.org/10.1149/F2.1381902jes

Impact of a Titanium-Based Surface Coating Applied to Li[Ni0.5Mn0.3Co0.2]O2 on Lithium-Ion Cell Performance

ACS Appl. Energy Mater. 2018, 1, 12, 7052–7064

Publication Date: 15 November 2018

https://doi.org/10.1021/acsaem.8b01472

Electrolyte Design for Fast-Charging Li-Ion Batteries

Cell, Volume 2, ISSUE 4, P354-366

Publication Date: 01 April 2020

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.trechm.2020.01.011

Bridie Schmidt is associate editor for The Driven, sister site of Renew Economy. She has been writing about electric vehicles since 2018, and has a keen interest in the role that zero-emissions transport has to play in sustainability. She has participated in podcasts such as Download This Show with Marc Fennell and Shirtloads of Science with Karl Kruszelnicki and is co-organiser of the Northern Rivers Electric Vehicle Forum. Bridie also owns a Tesla Model Y and has it available for hire on evee.com.au.