If you can see the horizon clearly for the first time, you’re not hallucinating: that’s what a reduction in air pollution unveils. And you aren’t the first person to notice it.

The peaks of the Himalayas have become visible from parts of India for the first time in decades, and residents of Delhi have recently shared photos of the India Gate War Memorial in full clarity, bereft of a smog filter which normally blankets the city and its landmarks.

Meanwhile, Los Angeles is reporting the longest stretch of clean airthe city has seen in a generation. It’s being seen the world over, with one expert asking the question “are we looking at what we might see in the future if we can move to a low-carbon economy?”

Sadly, this current dose of clean air is an unintended by-product of a global pandemic. The world’s population is in lock-down and off the streets, with economies going into hibernation as we understandably prioritise the health of the vulnerable.

Yet while the virus will eventually pass, the clean air does not have to go with it. We can make the clear view of our horizons permanent if we make the right choices on technology and infrastructure once the light at the end of the tunnel emerges. And for the sake of our health, the choices we make will be critical.

The main effect of breathing in raised levels of Nitrogen Dioxide (NO2) – which is caused by the burning of fossil fuels – is the increased likelihood of respiratory problems. Normally these are long-term issues, which are serious enough.

But the research stemming from the current pandemic indicates the levels of NO2 may be exacerbating incidents of COVID-19 infections.

Recent analysis from researchers at the Harvard TH Chan School of Public Health in Boston indicates that COVID-19 has had more of an impact in areas where there has been a high- level of air pollution.

The researchers, which analysed air pollution and Covid-19 deaths up to 4 April in 3,000 US counties, covering 98% of the population, found that a minimal increase in particulate matter in the air in the years leading up to the pandemic is “associated with a 15 per cent increase in the COVID-19 death rate”.

More research is being called for into the effects of air pollution on those infected with COVID-19, led by RIVM – part of the MCC Collaborative Research Network, a network of researchers from more than 40 countries around the world – which is looking to conduct investigation into “the contribution of air pollution to the severity of the COVID-19 outbreak”.

Further, the evidence is showing what is causing the pollution, and there’s a good chance one of them is parked in your garage

Fewer petrol vehicles, far fewer particulates

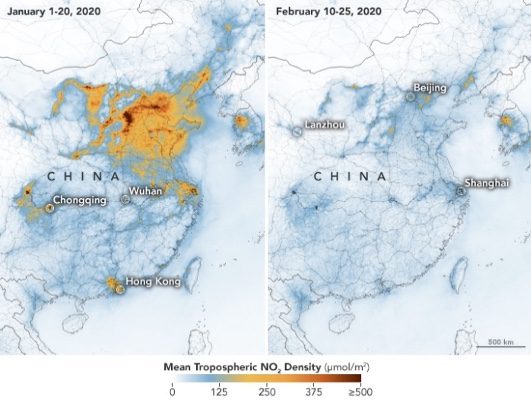

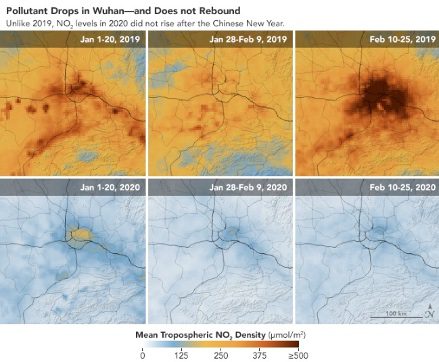

Satellites which chart man-made pollution across the world began to see a noticeable drop in pollution levels once cities began to undertake isolation and lockdown measures. Maps recently released by Descartes Labs use satellite data to track the steep changes in air quality, and found that in March and the first week of April, NO2 pollution fell 33 per cent In Los Angeles.

Some of this will be linked by many to a drop-in industrial activity – such as manufacturing and refinery – due to lockdown and isolation measures. However, the evidence is beginning to emerge that the lower pollution levels are in fact a result mostly influenced by a lower incidence of petrol-burning vehicles on our roads.

A BBC report in April revealed a stark drop in nitrogen dioxide across the United Kingdom, and in areas with high vehicle traffic but no industrial zones. “We’re seeing the reductions are greatest in areas most heavily-influenced by road traffic, so city centres, roads in London, Birmingham and other urban centres,” William Bloss, a professor of atmospheric science at the University of Birmingham, told the BBC.

In Australia, the cause of nitrogen oxide levels, particularly in city areas, is put down to motor vehicle exhaust, with 80 per cent of the NO2 levels estimated to be caused by the burning of vehicle fuel according to the Australian Government’s Department of Agriculture, Water and The Environment.

So, what’s next?

The evidence strongly suggests that pollution can be curtailed once we reduce our reliance on internal combustion engine vehicles in our everyday lives.

People are beginning to take notice. A recent survey found that only nine per cent of Britons want to return to life as normal after the end of the lockdown, with 51 per cent of respondents noticing cleaner air, and 27 per cent noticing more wildlife since the lockdown began.

An additional survey in the United Kingdom found that the improvement in air quality has UK drivers reconsidering plans to own an electric vehicle (EV): of those surveyed, 45 per cent said they are now thinking of switching to an EV.

As the world rebuilds, there is an opportunity to re-build in such a way that we ensure this clean air is not a blip on our historical radar. Each person who uses a vehicle can make a choice that has an immediate impact on the environment, whether it is to use a green taxi, purchasing an electric vehicle, or limiting the travel they take for work.

Governments can also play a role, and some already are: the NSW Government’s recently-revealed plan to fast-track EV uptake and supporting the rollout of publicly-available fast chargers is a great step forward, while Queensland is set to expand its state-wide “electric super highway”.

Through this crisis we have proven to ourselves that we can adapt our way of life for the greater good of the planet and its people – we are choosing to slow down and isolate to save our health, and the unintended consequence is that we have proven we can also positively affect the health of the environments in which we live.

It’s that last lesson we need to heed – fewer petrol vehicles on the road is clearly leading to cleaner air, and that’s something we have all achieved together in a matter of mere months. We can make this clean air a lasting effect, through the choices we make tomorrow.

David Finn is Chief Growth Officer and Founder of Brisbane-based EV charging company Tritium.