Range estimates for electric vehicles (EVs) – and for that matter, vehicles in general – are often the source of contention.

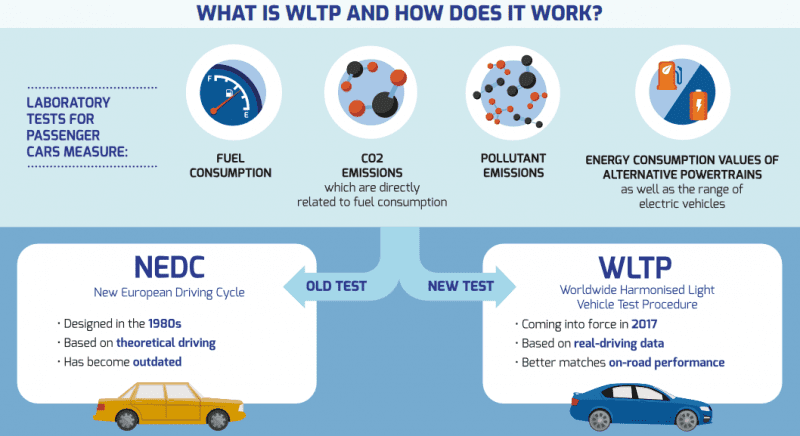

However, despite appearances, these estimates are not plucked from thin air. The generally quoted figures are normally derived through one of three international testing standards. These are:

- NEDC (New European Driving Cycle),

- WLTP (Worldwide Harmonised Light Vehicle Test Procedure) and

- US EPA (Unites States Environmental Protection Agency).

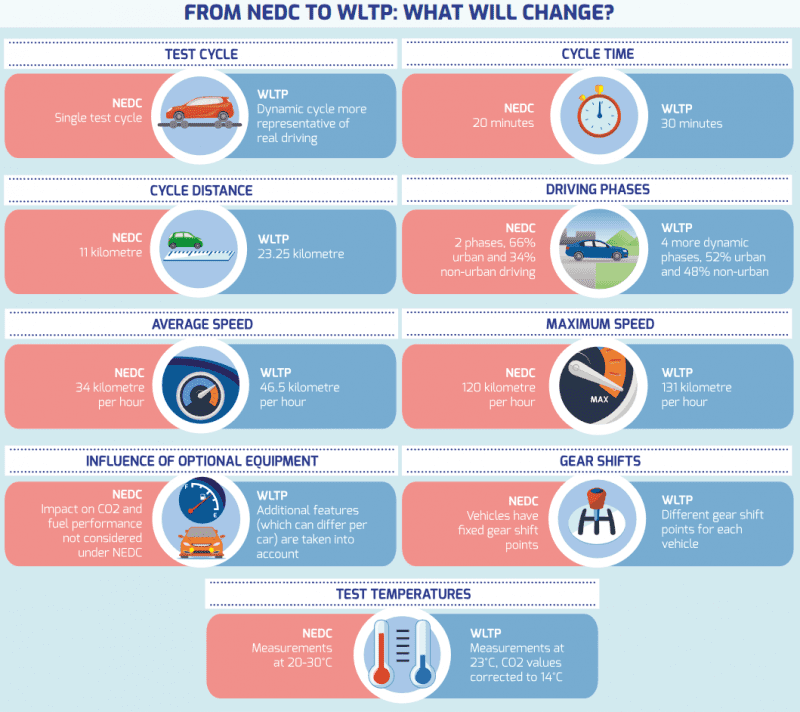

These three test cycles vary as to what proportions of city/country driving are included, as well as the defined climatic conditions. Naturally, the European test cycle tends to favour inner city and suburban driving, whilst the US one tends to include more outer suburban and highway driving trips.

By the way, the reason two European standards are bandied about is that WLTP is progressively replacing NEDC for new vehicles as they come onto the European market from September 2017, and all new vehicles in Europe must display WLTP figures from September 2019.

As background: NEDC is notorious for producing figures around 30% above ‘achievable’ distances – particularly so towards the end of its reign.

This was partly to do with the NEDC test cycle becoming ‘too’ settled, as well as rather theoretical. Together, these two factors led to auto manufacturers became quite adept at gaming the system to produce cars optimised to the tests. (And don’t forget VW’s outright cheating of the test cycles – termed ‘Dieselgate’).

As a result of the perceived failings of NEDC, the WLTP test cycle was introduced for European use late in late 2017 to provide more ‘real-world’ estimates for European driving conditions and usage.

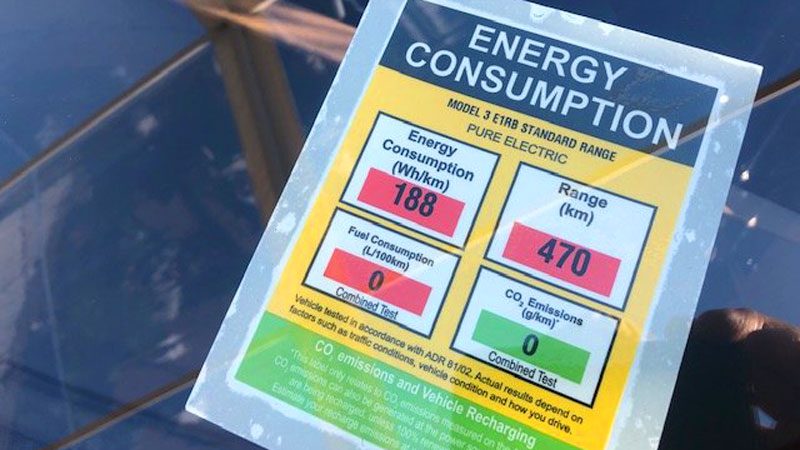

Here in Australia, we effectively use NEDC figures – and hence the rather optimistic EV ranges found on the Australian Green Vehicle Guide website (https://www.greenvehicleguide.gov.au/).

This is quite annoying, but a result of the Fuel Consumption labelling requirements under Australian Design Rule 81/02 — Fuel Consumption Labelling for Light Vehicles) 2008 being written before the introduction of WLTP. Consequently, our standards are closely related to NEDC.

This means NEDC is effectively the current Australian test cycle applying to showroom labels and the Green Vehicle Guide website. (Note: many auto manufacturers here in Australia are quoting WLTP figures in their advertising material for their EVs).

As mentioned above – NEDC is notoriously around 30% greater than what the ‘average’ driver achieves. So how can one find out what a realistic EV driving range is?

This is where the Environmental Protection Agency in the USA comes in. On the other side of the Atlantic from Europe, the US EPA has long set its own and very different set of vehicle consumption testing standards.

Widely regarded as more stringent and realistic – US EV drivers regularly report that they can easily achieve (and even sometimes exceed) the US EPA range figures. As US driving patterns are more akin to Australian ones – they are also more likely to be achievable here in Australia.

Therefore – when researching the range of a new EV to buy – I would suggest trying the following strategies for ensuring your chosen vehicle is likely to meet your driving needs:

- Check which test cycle the range estimate was made under. (If NEDC, subtract 30% for starters!);

- For the WLTP range estimate, check the manufacturers advertising material – often they quote WLTP instead of NEDC, or go to a European website for the vehicle. (Remember when checking overseas websites to check the options, wheel sizes etc as these can differ to Australian delivered cars). By the way: whilst WLTP is closer to ‘real-world’ consumption, WLTP ratings are still up to around 10% too high for Australian conditions;

- If the vehicle is offered for sale in the US (which covers almost all EVs except Renault who do not sell vehicles in the US) – check the US EPA rating for an even closer range estimate.

It is worth remembering that any of these test standards are still good for comparison between vehicles. What you must do is to check you are comparing ‘apples with apples’, i.e. when making comparisons, always ensure you are using the same test cycle (NEDC, WLTP or US EPA).

Ultimately though, fuel/energy consumption is a very individual thing. Getting a rating that reflects your individual usage is a bonus – but checking the rating system that your chosen EV is tested under certainly helps avoid disappointment.

Bryce Gaton is an expert on electric vehicles and contributor for The Driven and Renew Economy. He has been working in the EV sector since 2008 and is currently working as EV electrical safety trainer/supervisor for the University of Melbourne. He also provides support for the EV Transition to business, government and the public through his EV Transition consultancy EVchoice.