Consider these two statistics:

No 1: When asked, more than one third of Australians say that – given the chance – their next passenger vehicle purchase will be electric. More than two thirds think the shift to electric is inevitable.

No 2: In the first two months of 2019, sales of new petrol and diesel passenger cars in Australia slumped a stunning 21 per cent in February, versus a year ago. Overall new vehicle sales, according to the Federal Chamber of Automotive Industries, were down 9.3 per cent – a fall of 370 vehicles a day.

Are the two linked? It is hard to say definitively because the missing link – the actual switch to EVs – hasn’t yet happened in Australia because there are simply too few electric models available for purchase, bar the already sold-out limited offering of Hyundai Ioniqs and a range of vehicles priced at more than $100,000.

And it’s likely, as some economists suggest, that the downturn in petrol and diesel purchases is at least partly driven by the faltering economy, uncertainty about wages and jobs, the squeeze on borrowing and the fall in house prices which may make some prospective buyers feel less wealthy.

But here at The Driven we can’t help but think that something else might be at play. And even given the economic factors above, consumers are already thinking differently about their vehicle purchases.

They may not be able to get their hands on an affordable EV right now, but they may well soon.

Why not, then, hang on to the current vehicle a while longer. And if the transition to EVs is an inevitable as everyone says, then what’s the point of buying a fossil fuel car if its re-sale value is going to plunge in just a few years?

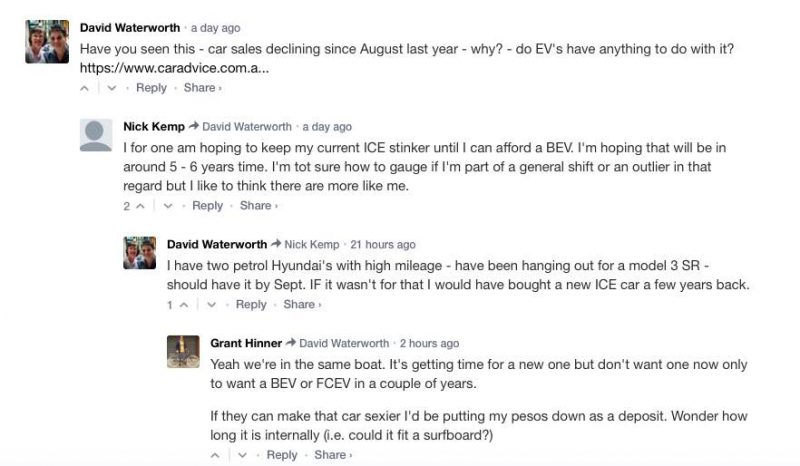

This at least, is reflected in some of the views posted in the comments section of this website in recent days, and following the initial reports of the plunge in fossil fuel car sales.

These are sentiments that we hear often. My next car will be an EV. That’s they way this author has been thinking for the last year as his current ICE vehicle drifts past the 10-year average in Australia.

And it stands to reason: away from the fringe-dwelling views of the conservative media, and the sheer idiocy of the federal government, Australians know a good deal when they see one, and they like new technology (see rooftop solar).

And there’s not much to dislike about EVs, even if many are still to get their minds across the range issues and re-charging.

(Interestingly, the only vehicle category to show good form in new sales in February were utes, which runs to a different commercial imperative because they usually belong to small business. But we think that the vehicles being developed by Rivian and Tesla will make this sector ripe for plucking too).

Australia’s uptake of EVs is pitifully low, due to the lack of options. In 2018, it represented less than 0.2 per cent of sales – just 1,352, not counting what might have been an equivalent number of Tesla sales (high cost Model S and Model X).

That will improve this year with the release of the Ioniq, the impending release of the Hyundai Kona SUV, the second generation Nissan Leaf, the Tesla Model 3, and other offerings from VW and Kia, all around the $50,000-$60,000 mark.,

There is some debate about how quickly the tipping point will be reached – will it be when the “life cycle” costs of EV ownership match those of petrol and diesel vehicles, as they have in Europe, or when the ticket price of the cars get close enough to make it clear that it is an economic and environmental no-brainer.

Norway illustrates how quickly the transition can occur. The government’s upfront rebates has helped narrow the price difference between EVs and fossil fuel cars quickly. And consumers have responded, with EVs now in Norway making up more than 50 per cent of monthly sales.

That’s how quick the transition can occur.

Which should put all Australian governments – local, state and federal – on notice. The recent Senate Inquiry into EVs highlighted the need for a plan, and for some incentives that could smooth out the transition.

But neither major political party would sign up – possibly because, in the case of the Coalition government, they are terrified of the carbon-tax-on-wheels campaign promised by the Murdoch media, and in the case of Labor, because they have their own plans to be unveiled during the upcoming election campaign.

The Australian Energy Market Operator has already sensed the change, and last year markedly upgraded its forecast uptake of EVs, suggesting that they could grab a 50 per cent share of new car sales within a few years, and 50 per cent of the total market by the 2030s.

That poses some interesting challenges for the grid. A 50 per cent EV fleet will likely add 30TWh to demand from the grid, or around 15 per cent. That is fine if it is spread out during the daya, because there is a lot of latent capacity – but not if it is focused at peak times.

It could also be a valuable resource, particularly as more EVs offer vehicle-to-grid services, which means EVs can be used to provide network services, and back-up power, if needed.

A 50 per cent EV fleet would offer 350GWh of battery storage – that is the equivalent of Snowy 2.0, paid for by consumers, and distributed around the grid to where it’s needed, without the transmission costs.

And, of course, it will need some thinking, planning and investment in charging infrastructure in regions and in cities, some thinking about the shift to automated driving, and what to do about the decline in petrol excise revenue.

Best to start now. The bottom has already fallen out of yesterday’s technology.

Note: Please click on our Models page to see which electric vehicles are and soon will be available in Australia.

Giles Parkinson is founder and editor of The Driven, and also edits and founded the Renew Economy and One Step Off The Grid web sites. He has been a journalist for nearly 40 years, is a former business and deputy editor of the Australian Financial Review, and owns a Tesla Model 3.